The Peaceful Revolution

True Confessions. Focused as I am on the scourge of Nazism, I hadn’t given much thought to the more recent history of East Germany – until I arrived at the Forum of Contemporary History in Leipzig. Before long, I began to understand the suffering of people living in the so-called German Democratic Republic – and the monumental effort that eventually overthrew this repressive regime.

The map above shows Germany’s divisions after World War 2, including the Soviet-occupied sector that became the GDR, whose logo is on the right.

In 1949, the year I was born, the Soviet-controlled zone of Germany officially became a nation of its own: the German Democratic Republic or GDR. Its people were still reeling from the devastation of World War 2, from massive supply problems and housing shortages. The word “Democratic” in its name was a sham. Following the Soviet lead, the GDR squashed dissent and consolidated the parties into one: the Socialist Unity Party (SED). There was no separation of powers, no democratic elections, no free press. It was a dictatorship. And like all authoritarian regimes, it had to have a public enemy. So the government portrayed itself as the righteous defender against the National Socialists (the Nazis). Within three months, a Ministry of State Security (better known as the Stasi) created secret police that would use all means necessary to secure party control. The Stasi could arrest alleged enemies of the state, conduct its own investigations, and run its own prisons.

The Stasi at work, quashing the 1953 uprising,

Was there resentment? Yes. East Germans characterized elections as “going to fold a piece of paper” because that is all they could do. The outcome was predetermined. Four years later, store shelves were still half-empty. Ordinary people were frustrated by their government’s focus on heavy industry instead of everyday consumer items. When Stalin died in 1953, many hoped their lives might improve, but the SED Party kept pushing. To counter the supply problem, they increased work quotas. That was a step too far. Hundreds of thousands in over 700 cities and towns took to the streets in protest. What does any good dictatorship do in reaction? The SED Party declared a military emergency, mobilizing troops against demonstrators and lining the streets with tanks, violently quashing the uprising. They blamed the West, and called it a Fascist Putsch – a word usually reserved for Hitler’s failed attempt at a coup in 1923.

Tens of thousands of East Germans fled, crossing the wall in Berlin. By the time the SED began to build the infamous Berlin Wall in 1961, three million had found their way out. Those who remained behind the “anti-Fascist protective wall” were caged in. Fleeing now meant risking one’s life.

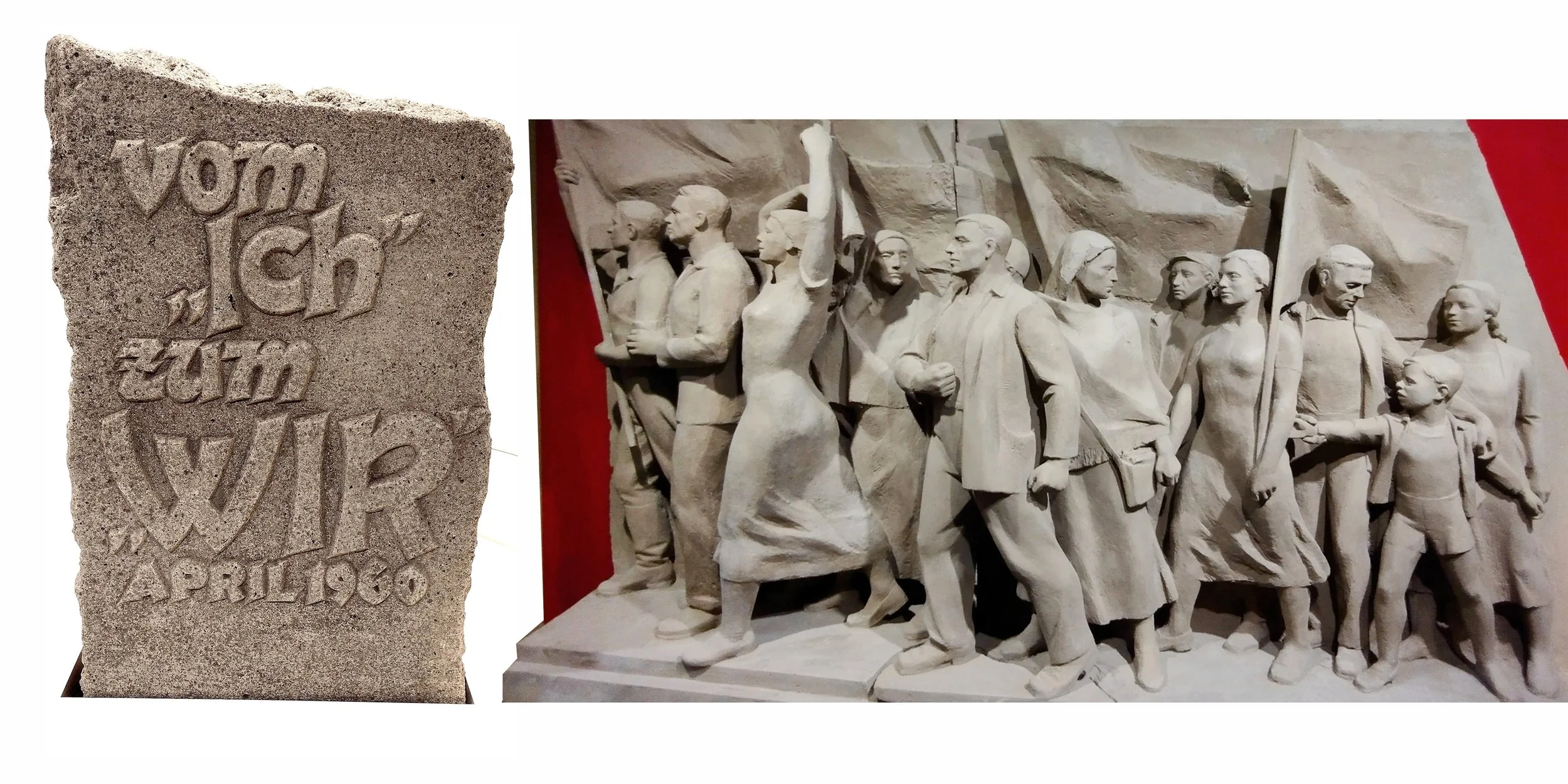

Left: GDR stone at museum Vom “Ich” zum “Wir” (From “I” to “We”) . Right: This relief is the version approved by the SED as a memorial for the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. It shows well-fed Communists liberating the camp. In fact, the artist’s original work showed emaciated prisoners liberated by American forces. Propaganda was more important than truth.

A stone at the Leipzig museum encapsulates the Communist philosophy: Vom “Ich” zum Wir, From “I” to “We.” The concept of placing community above individual desires sounds rather idyllic. But, in practice, personal freedom was non-existent. The government started merging fields, barns, cattle herds – everything agricultural – so they could manage it collectively and, theoretically, increase production. But that promise never materialized and, increasingly, people felt demeaned. Of course, money still trumped ideology; under-the-counter goods were reserved for “special” customers. But good quality tech products like color TVs and cars were hard to find and impossibly expensive for average people.

Regardless of simmering discontent, the SED was determined to foster loyalty, and what better way than in the classroom? Pre-schoolers sang songs about the National People’s Army. Children aged 6-13 became members of the Young Pioneers, learning to hate the warmongers (the West) and embrace “patriotic” values. In 8th grade, students were expected to join Free German Youth. Ideology-soaked education helped ensure the next generation would believe in – and be willing to fight for – the Communist credo.

A recreated classroom at the Leipzig Museum. The sign says “Study hard to honor our GDR.”

In 1968, the daily insult of authoritarian rule got personal in Leipzig when the East German regime decided to demolish the 700-year-old Paulinerkirche (St. Paul’s Church). The church had been a part of the university campus for centuries, and its destruction seems an intentional provocation from a government that needed to assert, again and again, that it was dominant over religion, the past, and the people. East German authorities were deluged with letters of protest that were summarily ignored – reinforcing the point that public opinion was irrelevant.

Beautiful Paulinerkirche in Augustusplatz in 1948, 20 years before its demolition by the GDR.

By the 1980s, Leipzig had two dubious distinctions: its air quality was the worst in the country, and its rivers were heavily polluted by industrial waste and foul-smelling sewage. The government, focused on production, did nothing. This environmental nightmare was another reason that Leipzigers would, finally, find their unique voice in the fight against repression. Another was the growing call throughout East Germany to loosen travel restrictions.

During Communist rule, a state-owned plant in Bitterfeld made Leipzig’s air quality the worst in the country. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons and Bundesarchiv.

Dissenters could rely on one place for protection: the Protestant Church, an institution that, from its inception, understood the nature of protest. For more than a decade, the pastors at Leipzig’s grand Nikolaikirche encouraged congregants to meet on Mondays to pray and talk politics. The meetings began to attract hundreds – and then thousands. In 1988, a determined group planned a march “memorializing” the contaminated Pleiße River. In one account, activists, unable to find a printing press, printed 300 fliers, sheet by sheet, through a wringer washing machine. By the summer and fall of 1989, momentum was building around the country and the Stasi took notice. Inspired by China’s crackdown in Tiananmen Square, the police were primed to use violence. Dozens of dissidents were jailed, including the pastors of St. Nikolas. Those Monday Meetings were proving too popular, and protesters were spilling onto Karl Marx Square. On October 2, peaceful marchers were beaten by police.

Wir Sind Das Volk banner displayed at Leipzig Museum, highlighting the use of the slogan over the decades.

On October 9, eight thousand people crowded into the church for the Monday Demonstration. From St. Nikolai Church to Augustusplatz, a whopping 70,000 courageous citizens marched, committed to both change and non-violence. They carried candles and banners saying Wir sind das Volk – We are the People. Six thousand armed police carried machine guns – but they held their fire. What could they do against such a massive number of peaceful demonstrators? What could have been a massacre became the inspiration for even larger protests. On October 16, the Leipzig numbers grew to 120,000. Berlin would soon follow suit. The Peaceful Revolution seemed unstoppable.

On October 9, the Monday Demonstration in Leipzig brought out 70,000 protesters. That number nearly doubled by the following week. Photo on left from City of Leipzig and photographer Sieghard Liebe

Of course, there were many factors contributing to the fervor. Thanks to Mikhail Gorbachev, the Iron Curtain had become porous, and thousands fled, fueling the desire for fewer travel restrictions. The East German government was getting the message. Under pressure, the SED leadership passed new regulations allowing limited travel abroad in the future. It was meant to appease the masses – and it might have worked, if not for one fateful error.

On November 9, the SED spokesperson held a press conference to talk about the new travel regulations that would allow GDR citizens to go to West Germany without advance permission. These were intended to take effect very soon – but not instantly. When a reporter asked when the new rules would be in place, the spokesperson referred to his scribbles, then responded, “Immediately. Without delay.” Those simple words took down a wall that had stood for 28 years. Whether it was a gaffe by an overworked bureaucrat or the impulse of a disillusioned official may always be the subject of debate; either way, its impact was monumental.

My husband, Pat, viewing the historic press conference exhibit at the Forum of Contemporary History in Leipzig. The scribbles on the enlarged memo to Pat’s immediate left were notes from Günter Schabowski, Secretary for Information of the Central Committee Secretariat, GDR.

West German TV stations broadcast the news: the Berlin Wall was opening. Within minutes, word spread to East Berlin. Thousands, and then tens of thousands, converged at the wall. Not expecting such crowds and without orders to do otherwise, the East German guards opened the gates. Brick by brick, the wall dividing east and west was dismantled.

In the United States, we often remember President Reagan’s encouraging 1987 speech at Brandenburg Gate in which he urged: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall.” But the people of East Germany did not hear those words of inspiration. Two years later, the peaceful protests that began in Leipzig were the real catalyst. It is certainly a lesson for our time: the power of numbers can make a difference. But – it took forty years of deprivation to build that momentum.

A view from the museum overlooking Naschmarkt Plaza, which includes the Bourse (Stock Market Exchange in center) and a statue of Goethe. “Nasch” is Americanized as “nosh” (snack).

I wish we could end the story there, at its happily-ever-after conclusion. But East Germany had been deprived for so long that it would take enormous effort and resources to rebuild it. Some citizens had craved reform but wished East Germany to remain separate. Even decades after the reunification of Germany, many East Germans still feel like the proverbial stepchild: underrepresented in government and underdeveloped economically. And because of Communist rule, East Germans never had the same kind of reckoning with the Nazi past as West Germans. In fact, many wondered why there wasn’t as much attention paid to their suffering - and they resented the feeling that West Germans had “won” reunification. Add to that the influx of immigrants from Syria and Afghanistan, a worldwide wave of populism and xenophobia, and you have a recipe for a spike in Neo-Nazi, anti-immigrant activity specifically in East Germany.

The slogan used by Leipzig’s brave protesters, Wir sind das Volk: We are the people, has been co-opted by those on the far-right, just as the right wing in this country have tried to hijack the American flag. Too often on this trip, I have been reminded of my father’s succinct words: the pendulum swings. But what happens when it swings too far? How many generations does it take to correct itself?

Palm fronds atop the Column of Peace are central to Saint Nikolai Church Square. The Peaceful Revolution is Leipzig’s proudest moment.

When I emerged from the museum, I saw the city with new eyes. Now I understood the palm leaves atop the Column of Peace, a symbol of the Peaceful Revolution of 1989. Now the massive Saint Nikolai Church, crammed with worshippers on Easter Sunday, was more than an impressive work of centuries-old architecture. It was a place that exemplified the power of perseverance and courage.

In the Market Square, just a block from the church, children were treated to human-powered rides and toasted almonds, jugglers and harpists. Adults considered splurging on an archery bow or, in my case, a hat to shield my eyes from the newly emerged sun. It was hard, as we headed by train for Berlin, to remember that all wasn’t right with the world. But graffiti along the train station walls kept me wondering what lurked beneath.

If you haven’t yet read In the Wake of Madness: My Family’s Escape from the Nazis, please consider buying an ebook or paperback at Amazon, ordering at your favorite bookstore, or asking your local library to purchase a copy. Rating and reviewing at Amazon and Goodreads helps a lot. Many thanks!