Layer Upon Layer

I did not come to Berlin as a typical American tourist, eager to see Checkpoint Charlie or the Brandenburg Gate or even the Holocaust Memorial. Frankly, I regret that I did not have time for many of Berlin’s famed “things to do.” It’s a complex, sprawling city filled with sections and neighborhoods that each have their own identity with layer upon layer of historical importance, a city unknowable in a mere four days.

World clock at Alexanderplatz: Photo by Florian Wehde on Unsplash. The TV tower in the background is the tallest structure in Berlin.

We arrived via U-Bahn at Heinrich Heine Straße, just outside our apartment, one unit in a high-rise that spanned a block and turned the corner. Under a gray sky, the world around me looked gray, too – stark, prefabricated concrete buildings built in the 1960s in typical East German fashion, now updated and extended to provide affordable shelter in a city where rents are rising fast. Despite my initial reaction, I came to enjoy our location in Kreuzberg on the edge of Mitte, immersing us in a real life Berlin experience rather than the curated luxury of a hotel. As avid walkers, we could reach most places on foot.

In Frankfurt, we had been warmly embraced by Tilman, the retired teacher who had deciphered my grandparents’ old handwriting, and his wife, Christel. That good will spilled over into Berlin, where their daughter, Kerstin, and her husband, Frank, make their home. They had read In the Wake of Madness: My Family’s Escape from the Nazis and were determined to make our journey meaningful. “Meet us at Hackescher Markt at 11am - by the revolving clock,” Kerstin texted.

We waited as instructed, admiring the low arches and ornate façade of the old railway station. Here, the first S-Bahn train arrived in 1882, carrying Emperor Wilhelm I. By then, Hackescher Market had become a center of Jewish intellectual and cultural life. Over the years, Jews exiled from other countries fled to the relative freedom of Berlin, and its population grew.

Walking slowly around the block, Kerstin was quick to point out the Stolpersteine embedded into the sidewalk. These Stumbling Blocks – handmade brass plates created by artist Gunter Demnig in 1992 – are placed at the last known residence of a person deported or murdered by the Nazis. Demnig’s original goal was to remember his Sinti and Roma neighbors in Cologne, but the concept quickly expanded to all victims of the Nazis. The Stolpersteine now number 120,000 in 30 countries – a decentralized memorial in which each plate is like a headstone, with the person’s name, date of birth and ultimate fate. In recent years, their use has been extended to memorialize those who fled and survived, as my parents did – a change that has not been without controversy.

“People all around Germany clean the Stolpersteine regularly,” Kerstin explained. “On the 9th of November to commemorate the 1938 Pogrom, Holocaust Remembrance Day in January, and the 8th of May, known as Liberation Day in Germany (VE Day in the U.S.).” It’s a gentle polishing process, done with much care. The thought of Kerstin taking time to do that endeared me to her even more.

Stolpersteine (Stumbling Blocks) embedded in the sidewalks of Hackescher Markt (Market) in Berlin Mitte.

I paused to read four plates, the fate of a single family: Walther Steinwasser, deported and murdered at Auschwitz; his wife, Margarete, suffering the same fate; their son Julius, fleeing to Palestine illegally; their daughter Ilse, deported to Auschwitz and liberated. A few houses away, I glanced down at the Aronsach family, all murdered at Riga. Sadly, in this section of Berlin, the Stolpersteine are plentiful. How close my maternal grandmother had come to such a fate.

L to R: Entrance to the 8 connecting courtyards (Höfen); appealing art nouveau touches of the Chameleon Theaters, which showcases circus arts; one of the small factories and workshops embedded in the courtyard buildings.

My mood quickly lifted as we approached Hackesche Höfe – a series of properties with eight connecting courtyards on Rosenthaler Straße. It is a lovely and lively place brimming with history. By 1905, the year my mother was born, Berlin was the most densely populated city in Europe, and the neighborhood of Hackescher Markt was at its heart. Soon after, an architect who fancied Art Nouveau developed these “Höfe,” mixing housing, textile factories, workshops, and stores – a recipe that sounds almost contemporary.

Our new friends and guides, Kerstin and Frank, in front of the movie house, a cinematic tradition dating back to the 1920s.

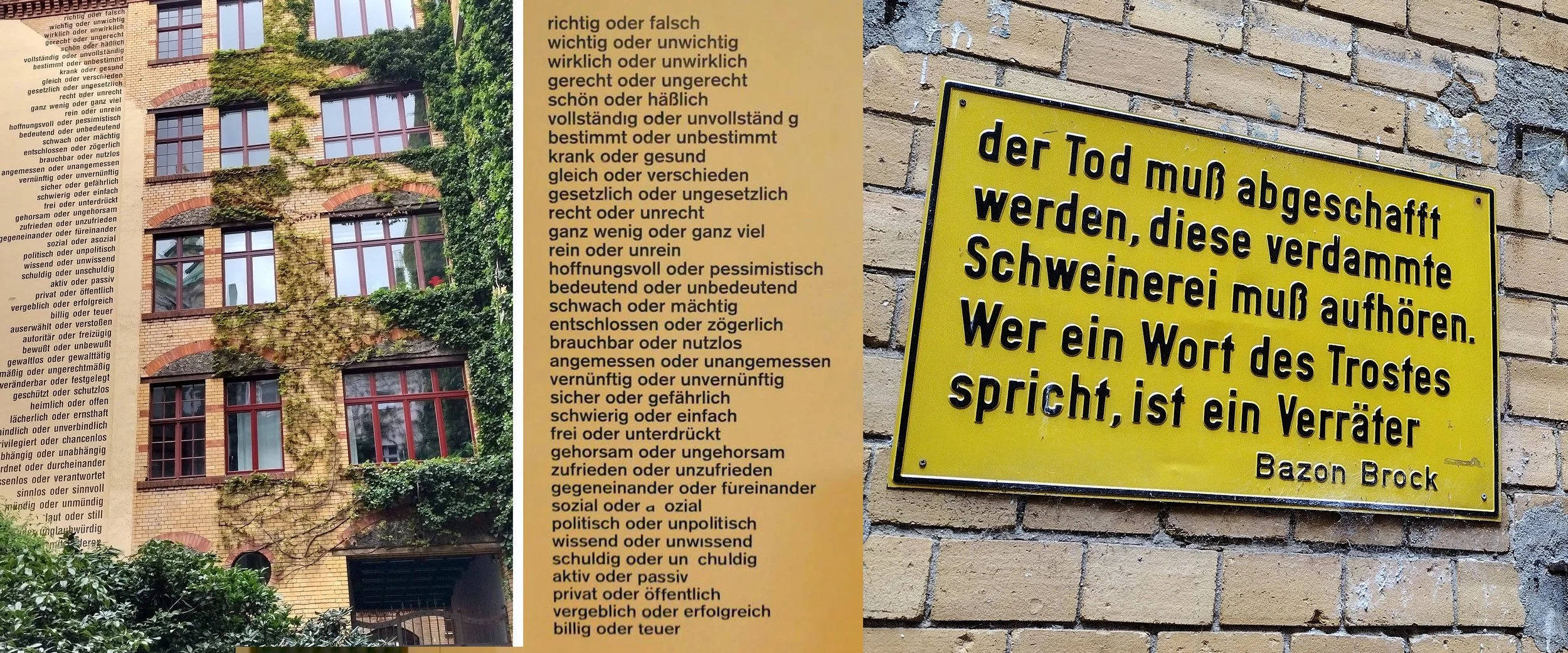

Word art is baked into the courtyards. On the left is a building that incorporates a work by Thomas Locher called “Opposites.” On the right is a sign by art theorist Bazon Bock who designed the sign to look like a high voltage warning. It reads: “Death must be abolished. This damned mess must stop. Whoever speaks a word of comfort is a traitor.”

The history of Hackesche Höfe took a dark turn when the Nazis came to power. In 1924, a new owner named Jakob Michael controlled a major share of the complex. In 1932, with antisemitism on the rise, he migrated to the Netherlands and then, the U.S., using a front man to maintain some ownership. One year later, Jewish properties were confiscated, and the Höfe were forcibly auctioned off. The Jewish community was dismantled: businesses, theaters, galleries, and schools destroyed, the nearby retirement home “repurposed.”

There are abundant signs within Hackescher Höfe explaining its Jewish history.

The courtyards sustained some damage from Allied bombing but much of their character was intact. Under the GDR, the Höfe were deemed the People’s Property and allowed to fall into disrepair. Soon after German reunification, more than fifty years after the Nazis seized the property, the heirs of Jakob Michael received restitution. Developers saw its potential; in 1993, a major restoration project began.

That complicated history seemed incongruous with the architectural detail and abundant greenery that surrounded us, leading seamlessly from one courtyard to another. Unable to resist a tiny store named Ampelmann, I was rewarded with a great story. In 1961, a stout green cartoon figure, jaunting happily along with a hat on his head to signal GO, and its red counterpart with his hands raised to his sides to signal STOP, were designed by Karl Peglau, a traffic psychologist, in an effort to get the attention of East German pedestrians. The cute figures became iconic, unique to East German society. When Germany reunified and the government tried to standardize traffic symbols across the country, East Berliners protested. They would give up their flag, but they would not abandon their beloved Ampelmann! Captivated by this tale, we bought Ampelmann socks for each of our grandchildren.

Traffic lights actually had to be redesigned to fit the more full-figured Ampelmännchen! It was interesting to find a symbol of East German life that was both nostalgic and apolitical.

Despite my appreciation for these well-scrubbed courtyards, I am struck by their contrast to Haus Schwarzenberg next door, a gritty holdover from a time when artists and bohemians established their roots – after the Berlin Wall fell but before gentrification began. Here, you can still get the feeling of an alternative culture all but erased from modern Berlin.

This scene gave me a taste of an alternative culture that once flourished in East Berlin.

Pablo Picasso as Superman certainly got my attention! Picasso and his complicated politics were perceived differently by East and West Germany, The East embraced his Communist membership but rejected his contemporary art. The West often dubbed him “apolitical” and fawned over his breakthrough art.

This alley is also the place where one man’s courage and humanity made a difference. Otto Weidt, sightless himself, established a factory here to manufacture paint brushes and brooms used by the military. His Workshop for the Blind employed Jews who, being both disabled and Jewish, were prime targets for the Nazis. He did everything he could to protect them from forced labor and deportation.

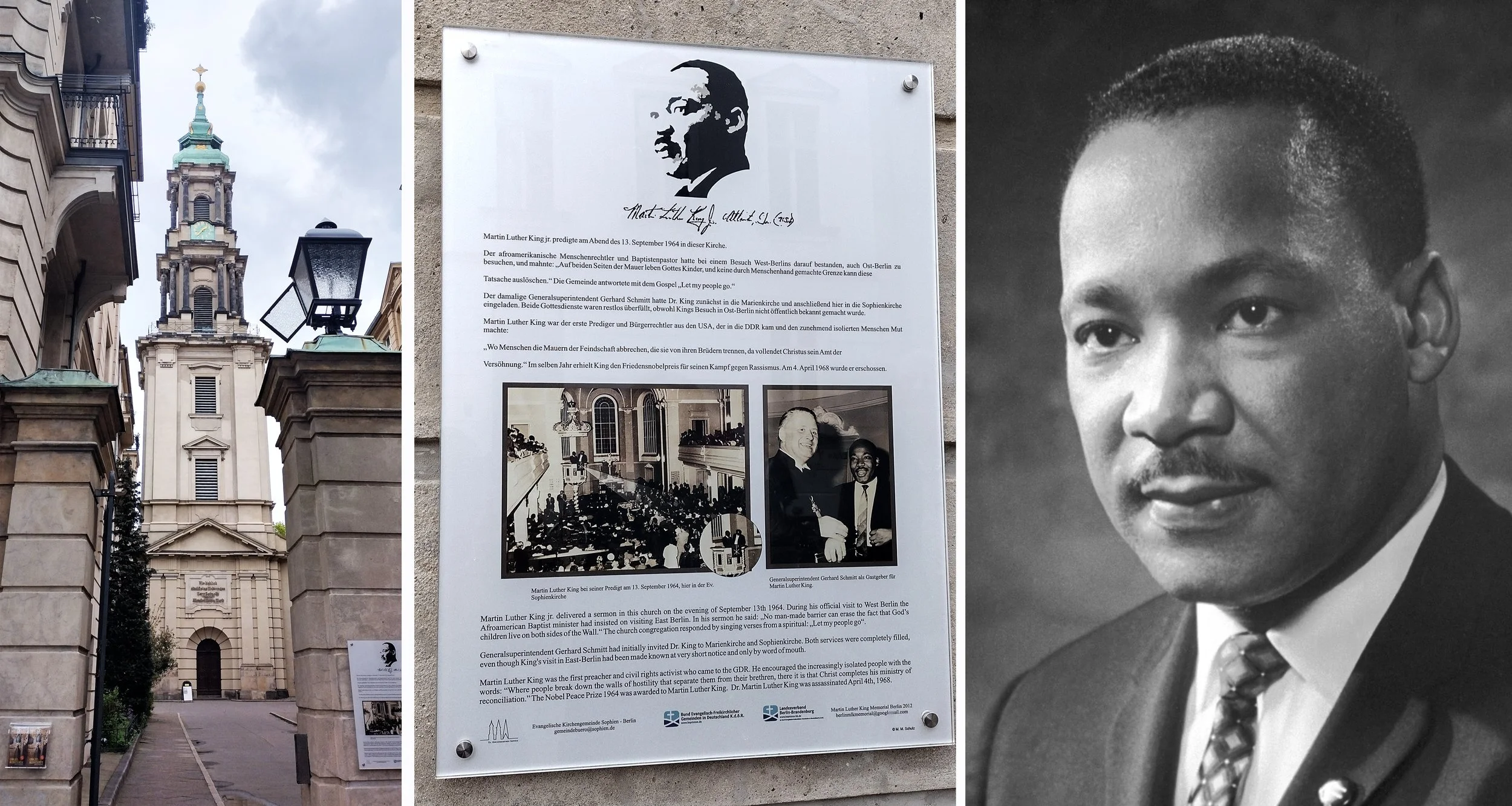

Imagine the excitement of the people of Berlin - especially East Berlin - when the esteemed civil rights activist arrived to deliver his message of unity. Of course, MLK Jr’s namesake is the German Protestant reformer, Martin Luther. Photo on the right is MLK in 1964.

Down a nearby alley we could see Sophienkirche, a church that might have escaped my attention if not for a plaque reminding passersby about its unexpected visitor in 1964. There, on Sunday, September 13 at 10pm, almost 2,000 people crowded in to see Martin Luther King, Jr., the American activist that months before had stood behind President Lyndon Johnson as he signed the Civil Rights Act into law. Although U.S. officials had taken his passport to prevent him from going to East Germany, King managed to get through Checkpoint Charlie with only his credit card. He felt a kinship for the East Germans, comparing the division of the nation to segregation in the U.S. “There is a common humanity that makes us sensitive to the suffering of all,” he preached. Amen to that.

Bullet holes and a missing building are reminders of a terrible past.

Near the entrance to the churchyard, Frank pointed out bullet holes and shrapnel scars, remnants of the intense fighting that marked the final days of the war. I imagined Soviet flamethrowers going house to house, the endless fire, rubble, smoke, and dust, the silence after days of roaring tanks, grenades, and machine gun fire. Across the way is the side of a building where once another building stood – a kind of open wound left as a reminder of what Nazism wrought. Today the memorial is called The Missing House. Mounted on the wall are 24 plaques listing the names and professions of former residents, many of them Jews. Much like Stolpersteine, they force you to consider the human cost of war.

Down the street, we passed another plaque in German, marking the site of the Jewish retirement home that the Gestapo turned into a detention center from which 55,000 Jews, the old and the young, were sent to Auschwitz and Theresienstadt concentration camps where, the plaque reads, they were “brutally murdered.” The Germans do not sugar coat or distort their sordid history. “Never forget,” it demands of onlookers. “Resist war. Guard the peace.”

This moving sculpture is a few yards from these old gravestones at the gate of the old Jewish cemetery.

Just beyond the plaque is the old Jewish Cemetery, desecrated by the Nazis, and a sculpture that touched me profoundly. I had been roaming amidst all this history, dry-eyed and sober, but the emotion of this sculpture broke all my defenses. Thirteen gaunt Jewish women, their hair shorn, their pain carved into bronze, stared at me at eye level. On their arms, at their feet, on the fence behind them, were stones placed to honor their lasting memory. It is a Jewish custom I remember from childhood, a more permanent memorial than flowers. I tearfully added a stone, thinking of the grandmother who might have shared this fate, the grandmother ripped away from me nevertheless by her escape to Chile.

L: The dome of the Neue Synagogue looms large. R: Interior of the Neue (New) Synagogue when constructed in 1866, built to house 3200 people.

Even from a distance, I could see the gold-ribbed Moorish dome that looks like it belongs in the Alhambra in Spain rather than on Oranienstraße in East Berlin. It is the New Synagogue (Neue Synagoge), the heart of the Jewish community since 1866. Despite the massive destruction of synagogues during the pogrom of November 9-10, 1938, this architectural gem was saved by two police officers, Otto Bellgardt, who intervened as a Nazi mob set fire to the interior, and his superior, Wilhelm Krützfeld, who covered it up. They must have recognized the synagogue’s historic beauty. Almost completely destroyed by Allied bombs, it was later reconstructed to its former glory. On the corner sits an Old Post Office built a decade after the synagogue.

An unadorned photo of the synagogue’s exterior, with posters of the hostages kidnapped by Hamas in the October 7 attack. A security guard patrols. In the first three months of 2025, Germany saw 1,047 antisemitic crimes. In Berlin, both left-wing and right-wing extremists contribute to the spike in antisemitic crime.

The beautiful Old Post Office was built to accommodate the horses used for horse-drawn mail coaches.

Our final stop in the Jewish quarter was AM Tacheles, once the site of the luxurious Friedrichstrasse arcades, then used by the SS, and neglected by the GDR. In the 1990s, the abandoned building became a magnet for artists who called it “Tacheles” – Yiddish for “straight talking.” Kunsthaus (Art House) Tacheles became legendary. “It was a lively mecca for artists,” Kerstin remembered from many visits after the wall fell. Its closure in 2012 was the end of an era. Today, it is home to a more contemporary - and commercialized - museum of photography, art and culture.

Stairwell art from another era, photo by Tim Krüger; the old department store with hints of its missing wall; renovated space on Friedrichstrasse.

We still had a full half-day ahead of us: a lingering glance at the Spree River and Museum Island, a drive through Brandenberg Gate and up Unter Den Linden, a stop at Humboldt Forum and the modest site outside of the university in the middle of the Plaza where students burned thousands of books deemed “un-German.” The year was 1933. More than a hundred years earlier, Jewish writer Heinrich Heine had said, “Where they burn books, they will also, in the end, burn people.” His chilling words were prescient.

Statuary everywhere!. From top clockwise: Bode Museum along the Spree River; the “Dom” or French Cathedral; Humboldt Forum courtyard with photo of wooden foundation piles driven 10 meters into the ground 300 years ago; exterior of Humboldt Forum cultural center; Unter den Linden street sign; Brandenberg Gate; street view including TV tower, the tallest structure in Berlin.

It had been a long day. Frank and Kerstin insisted that they drive us closer to our home base. “Can you recommend any nearby restaurants?” I asked.

Frank veered up a nearby street, jumped out of the car, and peered over a wall. “I had to make sure the place is still there. It’s been years since we stopped here.”

We said our goodbyes to Kerstin and Frank, knowing we would see them again soon. Walking down steps hidden from view on street level, we were pleasantly surprised by a charming cafe nestled by a pond. In the late afternoon sun, nesting swans entertained us as we sipped on beer and recounted our day. What a city – its complicated history laid bare.