Living with Uncertainty

Living with uncertainty is an unspoken undercurrent at the Jewish Museum of Berlin, following the visitor with unsettling persistence. It is a familiar feeling in these challenging times.

The advantage of walking everywhere is that you notice things that would otherwise be invisible. On the second day of our Berlin visit, our destination was the esteemed Jewish Museum. Along the way, I was treated to a potpourri of urban life: a giant pixelated face on the side of a building; a bit of inspiring philosophy on an office window; a hooded crow that is half-gray, half-black. I was particularly drawn to a series of miniature astronauts that sit atop wooden pillars, a sculpture almost hidden amidst the greenery on the corner of a nondescript brick building. Decked out in their white spacesuits and gold helmets, they are carved from the same oak as their base. The artist dubbed his creation Seventies, harking back to a time that achieved great things, an era in which anything seemed possible. We have learned otherwise, the artist is quick to point out, and progress has not always proved to be a good thing.

A hooded crow, urban art, and a touch of philosophy.

Seventies is the work of Albrecht Klink. Astronauts were a popular theme here. In another part of Berlin, a monumental cosmonaut floats on the side of a building.

As we turned the corner of Lindenstrasse, the museum’s disarming modern architecture was unmistakable. The building’s zinc and titanium exterior makes it almost impossible to distinguish one floor from another, while intersecting diagonal lines almost shout conflict and confusion. Surprisingly, we entered through an old baroque building that stands in sharp contrast, a 1735 structure that once served as the Prussian Court of Justice. But the entrance leads down through an underground passageway that evokes a kind of void, the emptiness left when the thriving Jewish community was ripped from the heart of Berlin. American architect Daniel Libeskind was very deliberate about all his choices. The zig-zag structure has many interpretations, but one thing is clear: you are meant to feel unsettled. The floors are tilted, the walls angular.

The extraordinary architecture of Berlin’s Jewish Museum is the work of Daniel Libeskind, who designed the zigzag structure one year before the Berlin Wall fell.

At the end of one passageway is the Holocaust Tower, a bare concrete silo in which two slanted concrete walls converge, punctuated only by a meager shaft of light. In the darkness, you are meant to feel the confusion of a refugee swept up by the horrors, unable to comprehend what is happening, why your world has so diminished.

The Holocaust Tower is overbearingly tall, stark, and dark.

Another passage leads outside to the Garden of Exile, a sloping plot of land with 49 tilted stone columns and uneven cobblestone paths. From each column are the branches of trees, now bare. One the one hand, it is a garden, and safety may be close at hand. But what you feel is claustrophobia, disorientation and uncertainty – emotions that must have been overwhelming for European Jews like my parents, forced to flee their homes, not knowing what the future would hold. Indeed, it is the fragile ambivalence faced by all refugees entering an unknown land.

The Garden of Exile might provide a path to freedom, but nothing is certain or straightforward.

At the end of another passageway is an installation called The Memory Void. On the floor are ten thousand heavy iron masks piled willy-nilly like bodies. Each mask wears a look of horror. The artist calls this installation Fallen Leaves – a reference to lives cut short. In my mind, that title, which refers to a natural cycle, stands in sharp contrast to the murder of millions. Visitors are invited to walk on the masks and gaze down at the silent faces. I could not. Would you?

The Memory Void: so many lives lost…

These symbolic installations are designed to evoke a visceral response, but it was the factual information that was most compelling and disturbing to me. One example was a map displaying acts of violence against Jews and Jewish institutions – cemeteries desecrated, synagogues vandalized, businesses boycotted and store windows defaced, riots, people attacked – all from 1930-1938, spanning the rise of antisemitism from Hitler’s early days through the November 1938 pogrom most Americans know as Kristallnacht. Many of those attacks were clustered around Frankfurt Am Main, where my parents lived before they moved to Brussels. The early waves of violence decimated as many as 2,000 Jewish communities throughout Germany.

Each dot represents an act of violence. The hand sits atop Frankfurt am Main, where my parents lived.

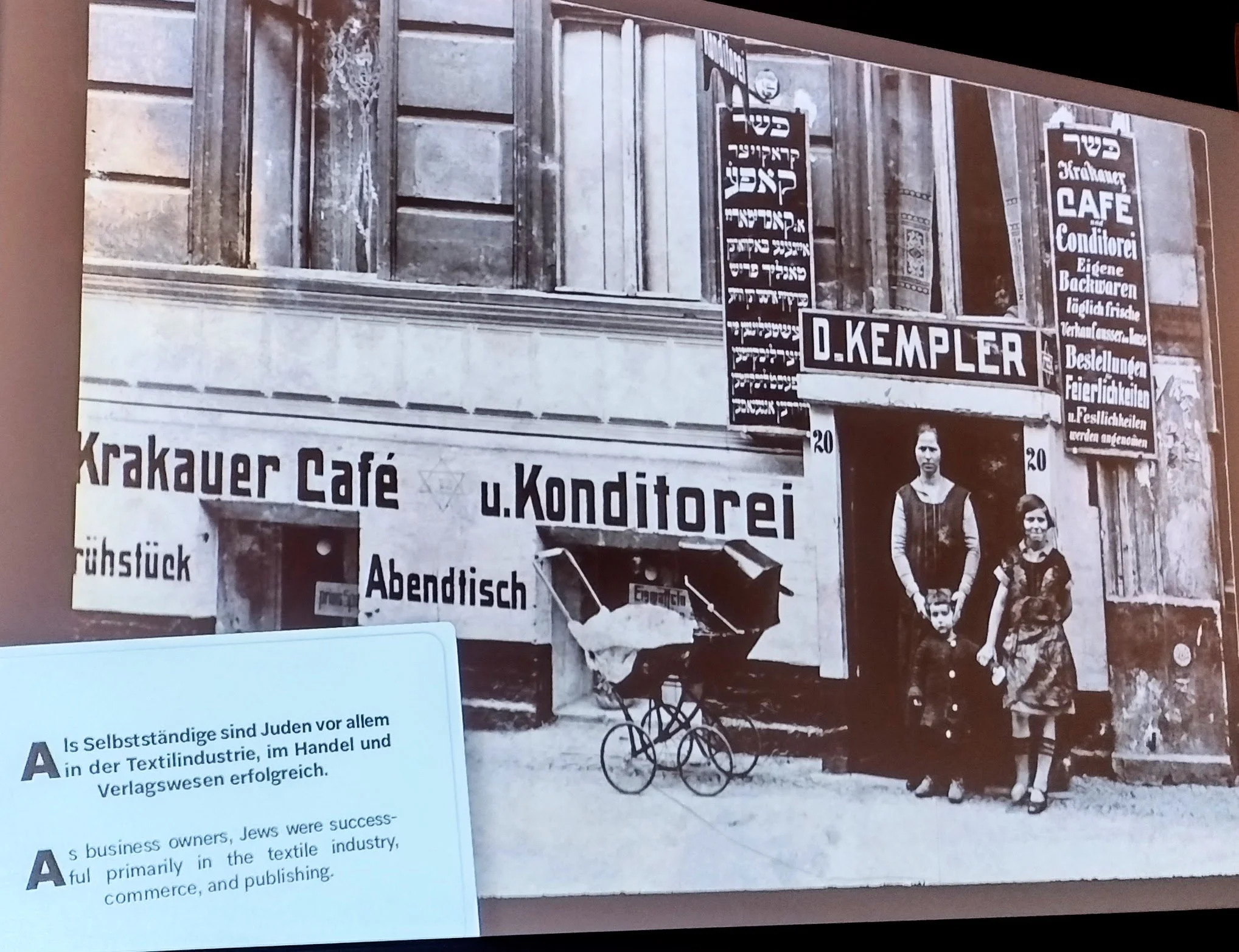

Those lives had everyday faces: actors and shopkeepers, musicians and publishers, department store owners and scientists. And those lives had prominent faces portrayed in Jewish art: Joseph Oppenheimer’s 1925 painting of Judge Karl Mensch and architect Ludwig Guttmann on their way to the opera in Berlin; Ludwig Meidner‘s 1931 portrait of rabbi and philosopher Leo Baeck who survived the Theresienstadt camp-ghetto; and impressionist Max Liebermann’s melancholy self-portrait. Liebermann lived on the shores of Wannsee, where Nazi officials later developed the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.” In 1933, he wrote to friends, “Like a dreadful nightmare, the abrogation of equal rights weighs heavy on all of us, especially on those Jews who, like me, had succumbed to the dream of assimilation.”

“Like a dreadful nightmare, the abrogation of equal rights weighs heavy on all of us, especially on those Jews who, like me, had succumbed to the dream of assimilation.”

Painting by Joseph Oppenheimer: On the Way to the Opera, 1925, portrayed a judge and an architect. Opera was very popular among German Jews in the 1920s. Jewish composers, conductors, and singers were integral to the culture. .

Portrait of theologian Leo Baeck, international leader of Reform Judaism. He survived the camp at Theresienstadt. Today, the Leo Baeck Institute in New York and Berlin is devoted to the history of German-speaking Jews. My book, In the Wake of Madness, has a home there.

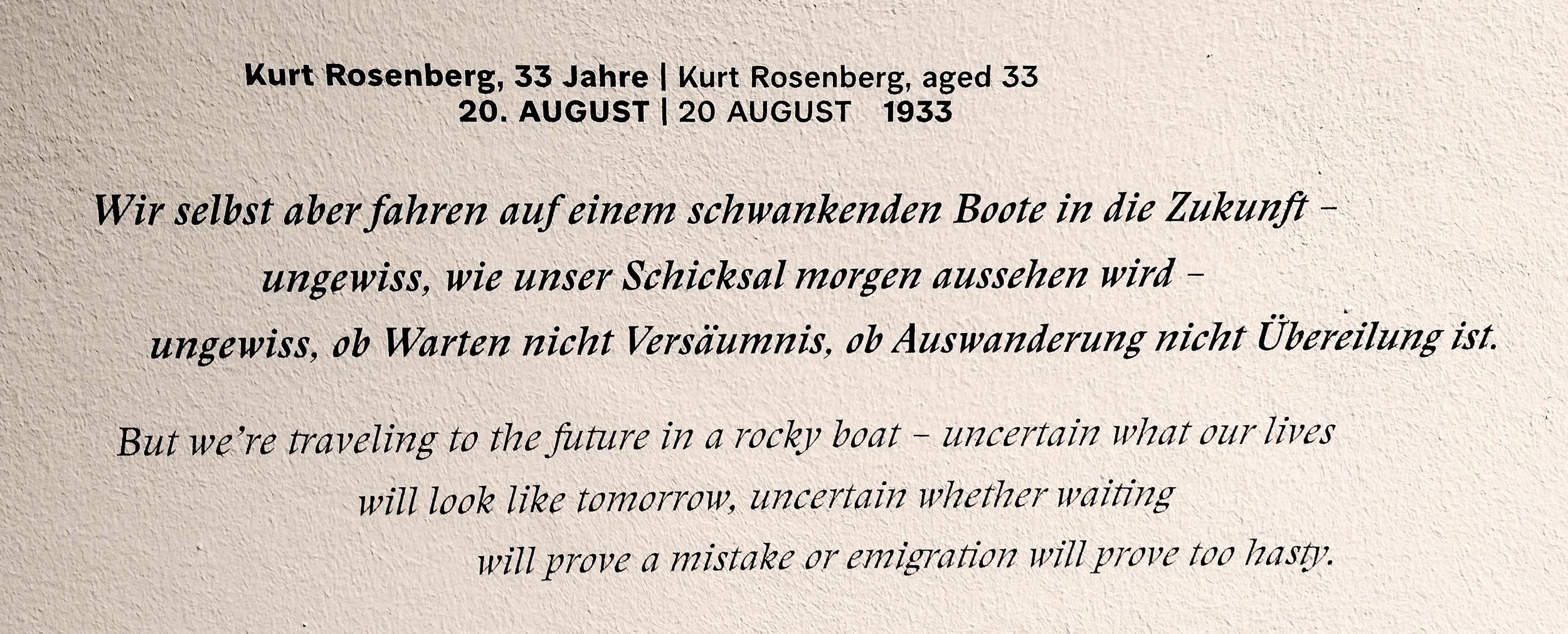

The year 1933 was the beginning of an awakening for German Jews. Scientist Albert Einstein professed, “As long as it is possible for me to do so, I will only live in a country where political freedom, tolerance, and the equality of all citizens under the law prevails.” Ordinary people started grappling with a question that feels altogether too familiar today: emigrate or endure? “We’re travelling to the future in a rocky boat,” said a young man named Kurt Rosenberg, “uncertain what our lives will look like tomorrow, uncertain whether waiting will prove a mistake or emigration will prove too hasty.”

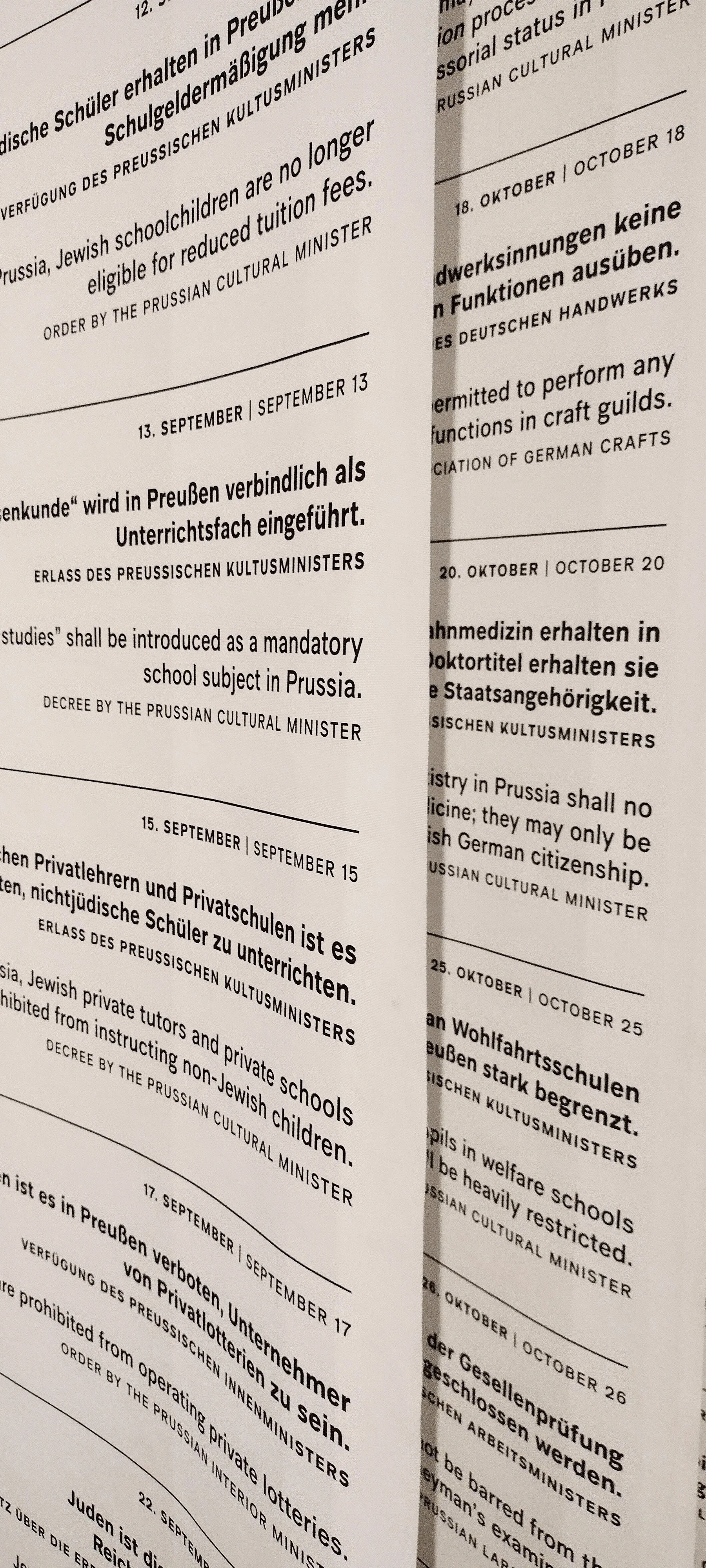

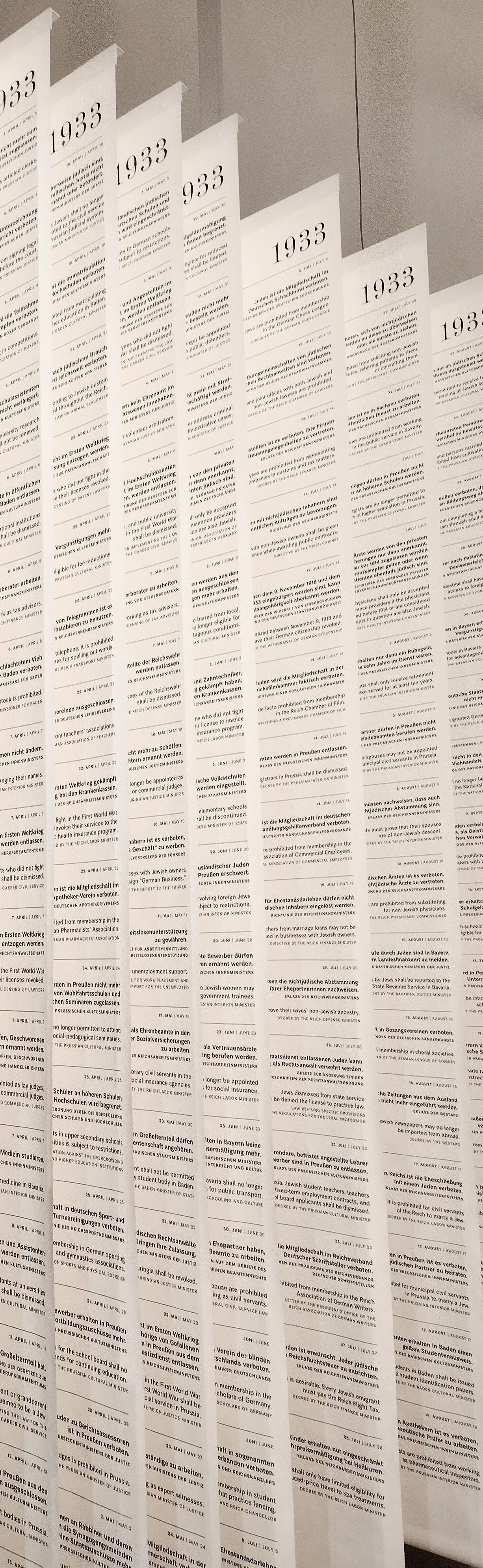

In an exhibit aptly called Catastrophe, scores of flags hang from tall ceilings, each one filled with measure after measure, law after law, restricting Jews, step by step. Some were national legislative measures; others were initiated by local governments or cultural organizations. I have read extensively about the incremental abolition of rights, but this display took my breath away, saddening and clarifying in equal measure.

THE CATASTROPHE ROOM

Left: An example of some of the measures exacted by the Prussian Cultural Minister. I hadn’t realized so many restrictions were placed locally as well as nationally.

Right: These flags show just a few months of the laws enacted in 1933 alone to restrict the lives of Jews.

In 1933, the year Hitler assumed power, the noose was already tightening. The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service excluded Jews and the “politically unreliable” from civil service. In Berlin, Jewish doctors were suspended from the city’s social welfare services. The legal profession no longer accepted Jews to the bar. Public schools limited the number of Jewish students, claiming overcrowding. The citizenship of naturalized Jews – and other “undesirables – was revoked. Jews were banned from editorial posts. In two years’ time, Jewish officers were expelled from the military, and the Nuremberg Laws (officially the German Blood and Honour and the German Citizenship Law) were enacted, stripping Jews of citizenship and forbidding sex or marriage by a Jew to a person of “German blood.” Everyone got into the act. Even the German League of Singers prohibited membership in choral societies. Soon, Jews couldn’t serve as teachers or veterinarians, as tax consultants or gun merchants. At the start of 1938, Jews were forbidden to change their names or the names of their businesses. Such easy camouflage would no longer work. A few months later, all Jewish women had to add the name “Sara” and all Jewish men had to add the name “Israel” to their names. No doubt that made it easier to invalidate the passports of all German Jews a few months later. The new passports would be marked with the letter “J.”

Throughout the countryside, signs would thank Hitler for what he was doing. This one says: “We don’t want to see Jews. They are our misfortune.”

All this happened before the November 1938 pogrom, in which thousands of Jewish businesses were damaged or destroyed, more than 1,400 synagogues set ablaze, Jewish homes vandalized, and Jews assaulted and killed in the streets. German police collected 26,000 Jewish men and sent them to concentration camps. This was not a spontaneous riot, a popular outburst of anger against Jews, as the Nazis claimed. It was a state-sponsored, orchestrated night of violence. My father got the message. From his relatively safe perch in Brussels, he read the news and made plans. Weeks later, he travelled to Amsterdam to file for his American visa. But the news was sobering. He would have to wait about two years and hope for the best.

I don’t have to tell you that things got a lot worse from there.

After such heaviness, I was grateful to experience the museum’s Staircase of Continuity, testament to the tenacity of the Jewish people. Along the way, visitors are treated to cartoon figures of Jews who have contributed to society in diverse ways, from historian Hannah Arendt to actor Leonard Nimoy.

Pat descending the Staircase of Continuity.

Pat and I enjoyed a cup of coffee in the light-filled atrium of the baroque-style courthouse before crossing the street to visit the Museum’s esteemed Blumenthal Academy and Library.

The interior was such a surprise!

What fun to see my book on the shelf in Berlin!

The old Prussian Courthouse opens up onto a peaceful greenspace.

The expansive library is part of the Blumenthal Academy containing 80,000 items on Jewish history, culture, art, religion and philosophy.

There, my book sits proudly on the shelves amidst 30,000 other volumes available to all. Fortunately for me, the librarian on duty was actually one of the archivists. After a short conversation about my book – and the discovery of those letters and documents that my parents saved – he said the museum might be interested in my collection. Something to ponder…

As we made our way back to our neighborhood, I noticed two banners hanging from a balcony with these messages: “DAS PROBLEM HEISST RACISSMUS” and “KEIN MENSCH IST ILLEGAL.” Even if you don’t speak German, you might guess what they mean. “THE PROBLEM IS RACISM. NO PERSON IS ILLEGAL.” The lessons of history hover over us like an impending storm.

It was wonderful to return to our idyllic café on the pond, share time with our friends, and watch the swans, graceful and majestic, work on their nests. If only everything could be that simple.

Have you read In the Wake of Madness: My Family’s Escape from the Nazis? If so, you know it’s an inspiring story that’s relevant for our times. Please consider gifting it to a friend or loved one. Thanks!

Click here to purchase on Amazon or order at your favorite bookstore.