A Young City with an Old Soul

Mural in an underground Leipzig tavern

Leipzig is a city of monikers. It is called the City of Music, Little Venice, City of Heroes, Trade Fair City, even Hypezig. What wonders would Leipzig hold for me? I had no family connections with the town, so it was a blank slate. I was looking forward to meeting up with our Omaha friends, Denise and Rich, and reimagining my travels with a lighter touch. After all, Leipzig is a lively city with a university vibe. But once you’re wearing those historical lenses, there’s no ignoring what’s in front of you. And what was in front of me, time and again, harkened back to the past.

Leipzig’s enormous train station doubles as a mall with 142 shops across three floors.

Among the first things that greeted me at the train station was a fanciful promotional sculpture for Auerbach’s Keller. I did not yet know that the popular restaurant and wine bar was a very old establishment that owed its fame to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, the poet and playwright that called it his “favorite wine bar” in 1765 when he was studying at the University of Leipzig. In fact, hanging in the tavern were paintings depicting astrologer John Faustus and his pact with the Devil. The legend inspired Goethe to write his most famous play, Faust; in turn, Goethe used Auerbach’s as the setting where Mephistopheles brings Faust to experience a more devilish side of life. Although Goethe was born in Frankfurt, Leipzig is only too happy to embrace all things Faustian, and the impact of both Goethe and his story are seen throughout the city. Appropriately, we reunited with our friends at a bar named Mephisto, and dined with their son and daughter-in-law at Auerbach’s that first night.

Auerbach’s ad at the train station; a struggling Faust outside the famous restaurant

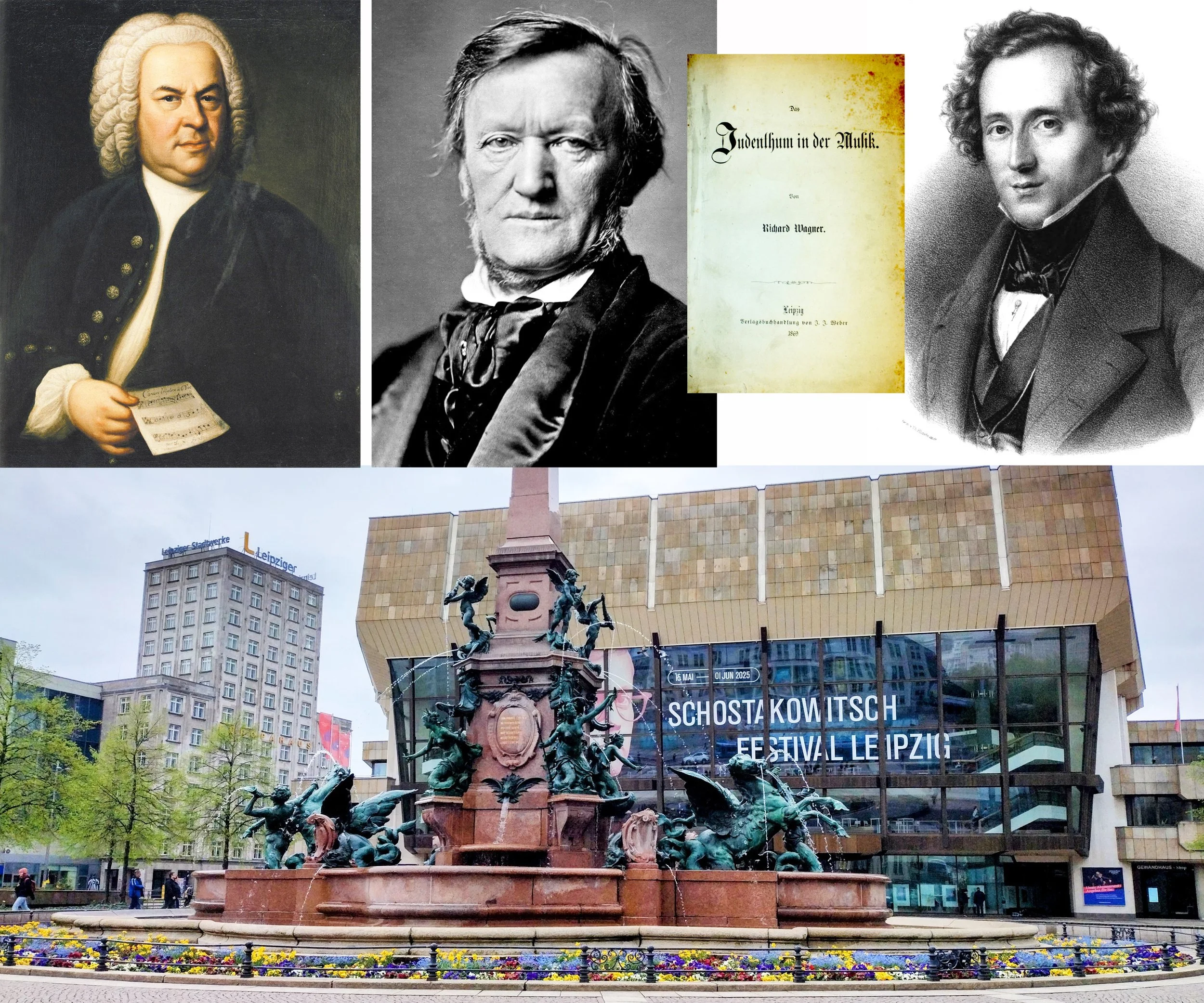

Leipzig also brags about its place in music history. Here, the brilliant and prolific Johann Sebastian Bach taught young students at Saint Thomas’s Church while churning out hundreds of cantatas and passions for the Lutheran Church. But the history of Jews in Germany seems to follow me into the most unexpected of niches. Leipzig is also the birthplace of Richard Wagner, whose antisemitic views led him to publicly denounce Jewish musicians as corrupters of German culture. Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy spent more than a decade in Leipzig as an orchestra conductor and co-founder of the Leipzig Conservatory; the last name of Bartholdy was added by his father, who had Felix baptized at age 7 despite his Jewish roots and his famous grandfather, philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. Gustav Mahler composed a symphony in Leipzig while working as a conductor, but his Jewish faith confined him to outsider status. Later in life, he converted to Catholicism so he could get a prestigious position with the Vienna State Opera.

Above, left to right: Bach, Leipzig’s “mediocre” third pick in 1722 for the position of music director; composer Richard Wagner and his antisemitic essay; Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, one of Wagner’s targets. Below, I was almost relieved to see the Russian composer, Shostakovitch, featured at Leipzig’s “Gewandhaus” or concert hall.

In truth, the only “music” I heard was the ringing of church bells in the historic public square. It was Easter weekend, and the famous churches of Saint Thomas and the grand, sprawling Saint Nicholas Church nearby, both originally built in the 12th century, competed in a cacophony of sound. While our friends spent time with family, Pat and I searched for Leipzig’s modest Holocaust Memorial. We crossed the busy Ring Road that circles the inner city, tracing where the town’s fortifications stood until 1763. I knew we must be close when we spotted a large banner that read NIE WIEDER IST JETZT: Never Again Is Now. It is a not so subtle reminder that antisemitism is on the rise in Germany as well as in the U.S. Without benefit of Google Maps, I’m embarrassed to admit that we couldn’t find the memorial. It was gray and cold, so we stopped at a lovely café for a bite and a bit of warmth. I picked up a brochure with the word Buch and quickly discovered that Leipzig is also known as Book City. As a center for printing and the book trade since the Middle Ages, Leipzig continues to be a publishing hub that now hosts Germany’s second largest book fair. Who knew? The brochure asks me “Was ist deine Geschichte? What is your story?” Indeed. Everyone has a story.

L to R: an old building along Ring Road and the kind of waterway that gives Leipzig its nickname of Little Venice; Nie Wieder Ist Jetzt (Never Again Is Now) banner near the memorial; brochure asking “What is Your Story?”

After coffee and a snack, we mustered the courage to ask our waitress about the memorial. “You probably walked right past it.” She pointed us in the right direction.

The inscription on the stone reads: In the city of Leipzig, 14 thousand citizens of Jewish faith fell victim to Fascist terror.

A half a block away, in front of a non-descript apartment building, sits a raised concrete platform with 140 empty bronze chairs representing 14,000 of Leipzig’s Jewish citizens who were segregated, persecuted and murdered during the Nazi era. The memorial is profound in its stark simplicity. In the background, where apartments now stand, Leipzig’s Community Synagogue had been erected in 1855. By the early 20th century, the city had become a thriving center for Jews, the largest in Saxony. Of course, the Nazis changed all that. The stately house of worship was desecrated and burned during the 1938 pogrom on November 9/10. The following day, it was demolished at the expense of its Jewish congregants. Jews were soon gathered and deported. By 1945, none remained.

Later I would learn that tens of thousands of men and women, boys and girls were taken to labor camps in Leipzig, forced to manufacture Nazi armaments and aircraft under the most deplorable conditions. These sub-camps, where many died of starvation, were part of the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp. Standing there in the midst of a bustling community, I could not imagine such horror – and didn’t want to try. The non-Jewish citizens of Leipzig also bore the price of Hitler’s madness, with 5,000 losing their lives during intense bombing by British forces. So much senseless loss…

Returning to the city center, we wandered through Leipzig’s famous passageways and hidden courtyards. You can sense the deep history here. Around 1165, Leipzig received city rights and market privileges, spurring commercial development. That status was solidified in 1497 when it received “Imperial Status” that offered protection for traders all over Europe. As commerce increased, passages were built to connect merchants’ houses and shops. These simple connections evolved into stunning shopping arcades and courtyards. Our friend, Stromer von Auerbach, proprietor of that Faustian wine bar, built an exhibition hall around his establishment in 1530. The courtyard, filled with upscale shops, flourished for centuries. In 1911, Anton Mädler, the owner of the Moritz Mädler suitcase and bag factory, acquired Auerbach’s property with a vision to expand while incorporating the beloved cellar. The elaborate design included an end-to-end glass roof, restored to its original glory after World War 2 bombings.

Examples of Leipzig’s famous passages including Mädler and Specks Hof, both originally constructed in the early 1900s.

We stumbled upon my favorite “secret” passages in Specks Hof, a series of halls originally built to display leather goods and jewelry even before Mädler’s team lifted a shovel. Renovated in the 1990’s, it is a treat for the eyes: a six-story historic building with surprises like barrel-vaulted passageways with copper ceilings, glass-covered atriums, and unexpected art.

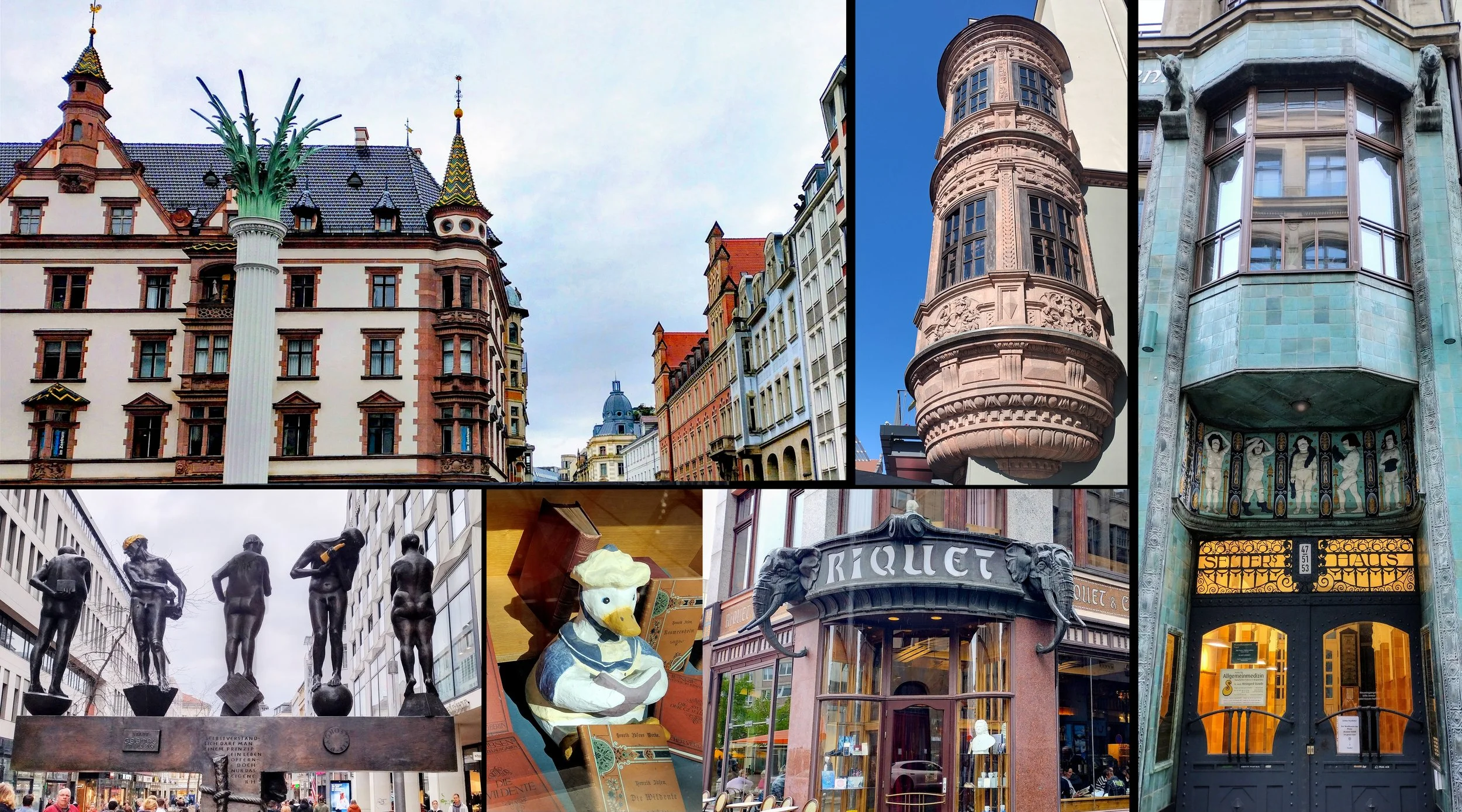

In fact, there is eye-candy everywhere. The New Town Hall, a youngster at 126 years old, boasts a fountain with a ring of children and animals spewing water. The Old Town Hall, built in the mid-16th century, competes admirably with its multiple wall dormers, decorative clock and copper steeple.

The Old Town Hall was rebuilt in 1556 in Renaissance style. The New Town Hall, built in 1905, is featured as a backdrop in Alfred Hitchcock’s film Torn Curtain.

The list is endless: the gleaming gold and white stock exchange dating back to 1678; ornate oriel windows that protrude from building corners; art nouveau flourishes on the Selters House; a sculpted elephant head protruding from a ritzy coffeehouse oozing historic charm; a most intriguing sculpture entitled Untimely Contemporaries that symbolizes the people of Germany grappling with two totalitarian regimes in the 20th century. A bookstore window earned a lingering glance with Donald Duck reading playwright Henrik Ibsen!

Clockwise from top: the palm frond of peace holds special meaning in Leipzig; an ornate oriel window; luscious Art Nouveau at the Selters Haus; a provocative statue; a bookstore window; the elegant Riquet coffee house.

The most unsettling sight was a piece entitled The Century Step – a man with one arm in the Nazi salute and the other in the Communist fist. It sits in front of The Forum for Contemporary History, demanding attention. We vowed to return.

The Century Man stands in front of the Forum of Contemporary History.

In typical fashion, we got lost on the way back to our Airbnb, but finally arrived safely in the dark. Our apartment was in an old building that now houses work spaces. In cloudy weather, it looked a bit dismal. Upon entering, we walked up deteriorating stairs and through a wide, concrete hall devoid of decoration with doors on either side leading to residences. It was a visual reminder that we were now in a town that was part of East Germany, neglected by decades of Communist rule. When we first approached, I could feel the guilt rise in me. How had I chosen such a spot? I do appreciate quirkiness, but this exuded no charm. But a wonderful surprise awaited us behind the door: a grand, high-ceilinged space with evocative art. Later I would think of it as a metaphor for this fascinating city that has endured so much and yet has found a way to flourish.

###

Next time: What Americans today can learn from Leipzig’s Peaceful Revolution

If you’re looking for a good read after a long day, check out my books. In the Wake of Madness: My Family’s Escape from the Nazis, is available on Amazon or you can order it at any bookstore. Burying My Dead, historical fiction set in Portland, Oregon, is also available as an ebook on Amazon.

After a long day, Pat is always ready for a beer - and sometimes a snooze.