Just Below the Surface...

When you take a moment to think about, every modern building is constructed atop layers of history. In my adopted hometown of Portland, Oregon, a portion of Lone Fir Pioneer Cemetery known as Block 14 was paved over in the 1950s. The county had planned for an office space on the site, but activists in the Chinese community recognized that the bodies of their ancestors still lay below, anonymous graves deserving of some long-deferred dignity. Fortunately, the construction was halted, and a proper memorial has finally been planned.

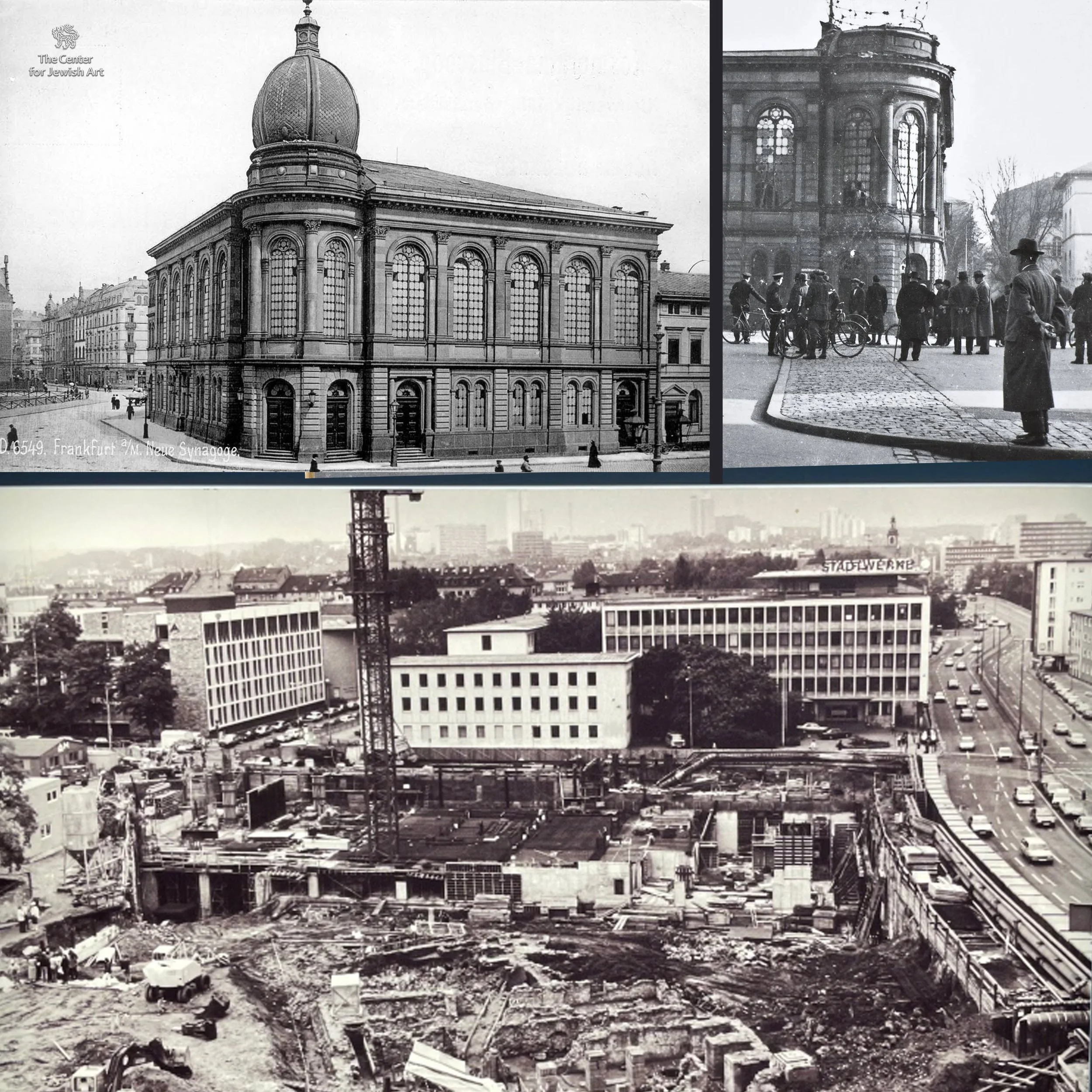

From upper left, the old synagogue at Börneplatz in 1917; looking at the destruction after the November 1938 Pogrom; the excavation site, showing the massive demolition and revealing the Judengasse foundations.

In 1987 Frankfurt, city administrators had similar ambitions. While excavating a site for a new public utility building, workers uncovered bits and pieces of nineteen houses that once were part of Judengasse, the alley or “lane” where Jews were forced to live in what was arguably the first European ghetto for Jews. Often, that dubious distinction is awarded to Venice, where Jews, expelled from Spain in 1492, were confined to a walled district in 1516. But the rediscovery at Börneplatz reminded Germans of their long, uncomfortable history with Jewry. This ghetto was first established in 1462, when Jews were forced to abandon their homes and their synagogue and “relocate.” What to do?

Journalists dubbed it the Börneplatz Conflict. I even found an article in an Associated Press piece dated September 20, 1987 that was published in the Los Angeles Times.

It had been little more than forty years since Hitler’s death. Germans had spent a couple of decades trying to get Nazis out of office and trying to forget. In the aftermath of war and loss, many felt more like victims than perpetrators. In 1963, twenty-two years after my parents landed in New York, my father applied for reparations. Germany’s reckoning with its horrible history was not instantaneous; it was a process. But by the 1980s, public discourse had become robust. A generation of German schoolchildren had learned about the Holocaust. This archaeological discovery would not be ignored. In the summer of 1987, fierce protests erupted in hopes of stopping the construction. Do not destroy history read one sign. Discussion not concrete read another. No future without a past. Because of what historians call the Börneplatz Conflict, a compromise was reached. The Customer Service Center was built, covering half the space where the 1882 synagogue and Jewish hospital had stood before its destruction in 1938. But five of the house foundations and two ritual bathhouses (mikvehs) were preserved, and, over time, a vital museum and memorial took shape.

Visitors can roam the foundations of five of the Judengasse homes and two mikvehs.

I didn’t know any of this as my husband and I stood outside the Judengasse Museum, the branch location of Frankfurt’s Jewish Museum that covers its earlier history. I had a lot to learn. Pat and I wandered the ruins, knowing full well that these stones dated back to the 15th century. I tried to imagine the sound of Yiddish being spoken within these walls, the comings and goings. I admit to a lack of imagination. I could not feel their presence. I have experienced this “vacancy” before, at Civil War sites and battlegrounds. Sometimes there’s no accounting for human emotions – or when they kick in.

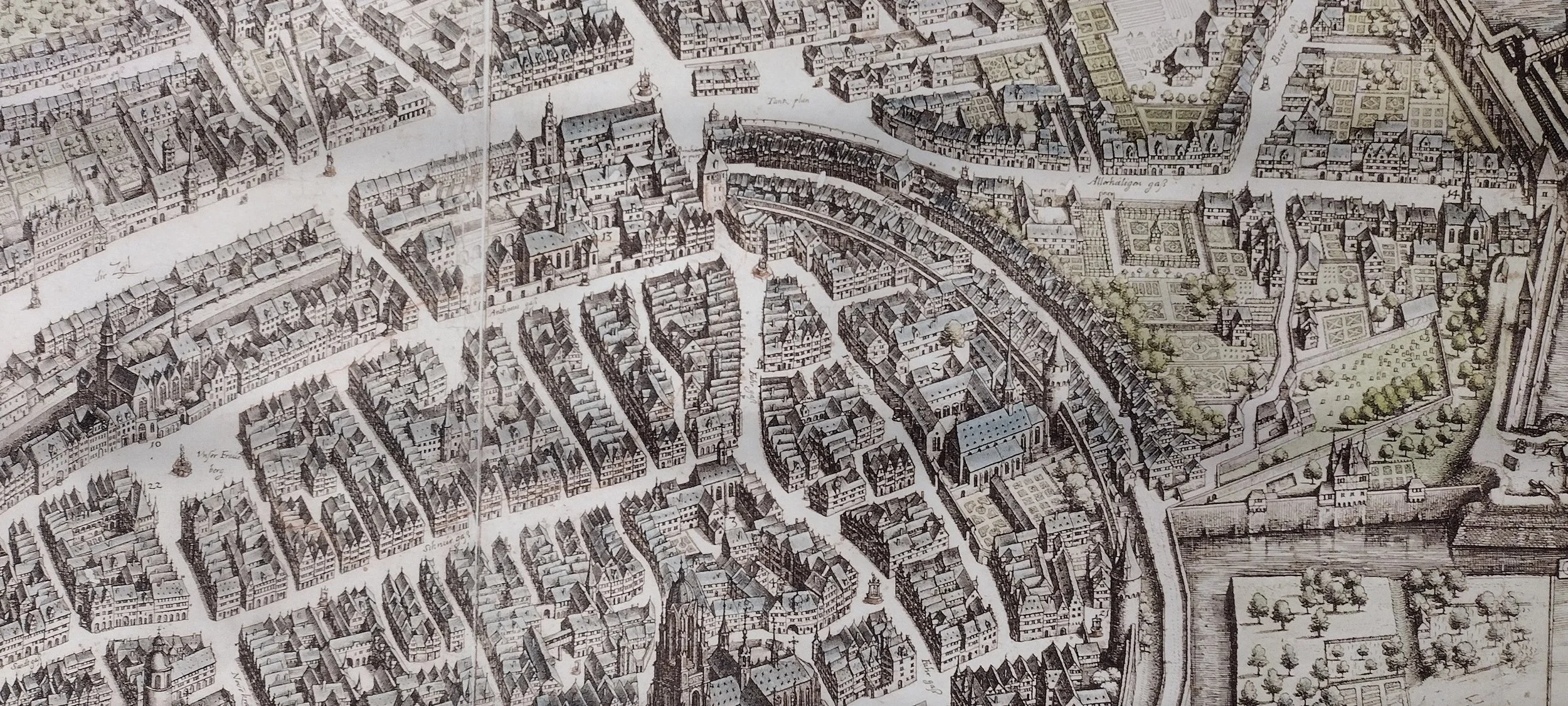

And then I looked at a map – a beautiful old map with detailed drawings of Frankfurt residences, stately churches, elaborate gardens, and the Main River winding through its heart. Only then did I see it: the wall built to keep the Jews confined, the narrow lane that had to accommodate every Jewish resident from 1462 to 1811, when the ghetto was formally abolished.

Do you see the Judengasse just outside the walls and the city gates? The houses are so "squished” that you can hardly discern them as houses.

The street, I soon learned, was only nine to twelve feet wide, leaving the community vulnerable to devastating fires. The walls extended for a fifth of a mile, the length of three football fields. In the early years, there were about a dozen structures, housing 100 inhabitants. By the 16th century, there were 195 houses. As the population grew, Jews had to build up, to divide and subdivide their homes into tall, narrow sections that could accommodate nearly 3,000 people. Dwellings were built behind dwellings so there were four rows of houses; upper stories were built over the lane until they almost touched each other. The smallest of homes was less than five feet wide. Jews and Christians could visit the other’s community during the day, as craftsmen and laborers often did, but three gates, locked at night and on Christian holidays, kept Jews in “their place.” For some inexplicable reason, the map made me viscerally understand.

Animal bones, probably from cattle, found at the excavation site along with dice that have been carved to fulfill the dice tax.

Among the tiniest of archaeological finds were animal bones found in a workshop, cattle bones processed into small cubes with numerical markings. These dice were a required toll that Jews had to pay to secure safe passage over regional borders. How could dice be intrinsically valuable? I wondered. As it turns out, they weren’t. Originally, they were given to customs agents to pass the time. Over the centuries, they were just another way to humiliate the Jews. But there were plenty of other taxes on Jews – a fact I learned when researching my family’s genealogy. More on that story at another time.

Outside the museum walls are the remnants of the Old Jewish Cemetery tucked out of sight within a thick canopy of trees. The oldest surviving tombstone dates back to 1272, even before the Judengasse was established. Many tombstones were desecrated in the 1920s, many more in 1938. In 1942, the government demolished as many as 6,000 more, piling up the rubble for removal. The space, they decided, would be better suited as a dumping ground for debris caused by air raids. Luckily, officials were diverted, and 2,500 tombstones remained.

The outer wall of the cemetery, extending unrelentingly to its vanishing point, has become a dramatic memorial for the Jews of Frankfurt who perished – not in centuries past but in the Nazi era. Stretched along the wall are 11,908 metal blocks, each commemorating a woman, man or child who had lived in Frankfurt and been murdered by the Nazis – almost 12 thousand souls who were not as fortunate as my parents and grandparents to have made their way to safety. As you can see, each one is like a miniature tombstone, engraved with a name, year of birth and, when known, the year and place of their murder.

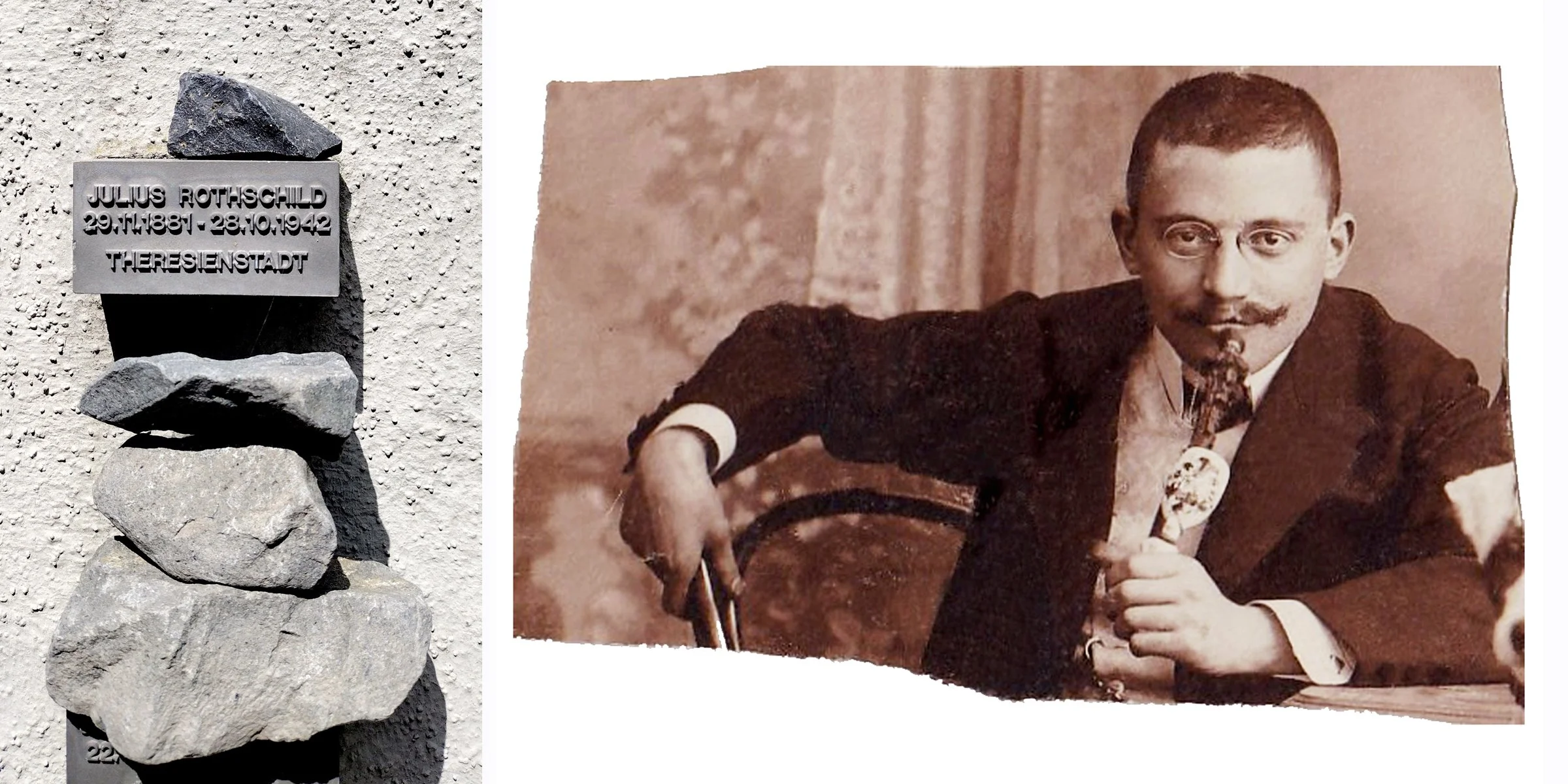

Pictured above, less than 200 plaques among the almost twelve thousand lining the memorial wall outside of the old Jewish cemetery.

As I wandered the wall, I realized that these names had been placed in alphabetical order. As far as I knew, my grandmother’s half-brother had lived in Frankfurt. He was a renowned chemist and metallurgist who, family legend has it, committed suicide at the Theresienstadt camp, hoping to prevent the Nazis from using his knowledge of explosives. So I sought out a plaque for Julius Rothschild, the uncle who had taught my father his profession of metallurgy, and, indeed, there he was. Someone – perhaps a long lost relative or colleague – had placed a stone upon his tiny grave, as is the Jewish custom of remembrance.

My maternal grandmother’s half-brother, chemist Julius Rothschild, and the memorial stone on the wall at Börneplatz outside the Judengasse Museum.

On the way back to our hotel, we crossed the Main River on the Iron Bridge, a pedestrian bridge adorned by thousands of locks of love and a handful of lovers. It was a far cry from our sobering visit to the Judengasse Museum and Memorial. We diverted to Schweitzer Straße, a street lined with Konditerei and Bäckerei, pastry shops and bakeries whose fresh ingredients and colorful displays made every walk a sensory delight. I lamented that they were closing for the day. I knew I would miss those shops, and I now understood why my mother would speak of them often. We also passed a pizzeria named Dick & Doof, German names for “the Fat One” and “the Silly One” – known to Americans as the comedy duo, Laurel & Hardy.

“Locks of love,” seen here adorning the Main River’s only pedestrian bridge, may have begun centuries ago in China or Serbia. Right: Apparently, Laurel & Hardy were difficult to pronounce or remember, so Germans renamed them. The duo was very popular in Germany in the early 1930s.

Down the road, we stumbled upon an unexpected sculpture: a hollowed out Dreidel – the spinning top that is used during Chanukah celebrations. Many American youngsters learn the “Dreidel Song” in school. “I have a little dreidel. I made it out of clay…” Beside the sculpture were the lyrics – and an explanation - in German, of course. The sculpture seemed remarkable in its unremarkability, a casual artistic addition to the streetscape. In preparing this blog, I finally translated the plaque, only to discover that a Jewish Children’s Home had been located nearby. During the war, an increasing number of young children were placed there, their parents hoping their children would be safe. But in 1942, forty-three children and their caregivers were transported to Theresienstadt Ghetto. The fun icon had suddenly become another poignant symbol of a dark time.

The street-corner dreidel was actually a memorial for the children and their caregivers who were deported from the Jewish Orphanage in 1942. The pre-war postcard from the children’s home is courtesy of Yad Vashem.

Back at the Living Hotel, I chatted haltingly with an affable young woman on staff as I refilled my bottle of Sprudelwasser (sparkling water). We chuckled over the difficulties of learning a new language, though I thought her English was großartig (terrific).

“Where are you from?” I queried, making small talk.

“Ukraine,” she said proudly.

The answer was unexpected, though it shouldn’t have been. More than 1.2 million Ukrainians have made Germany their home since the war with Russia began in 2022.

“Do you still have family there?” I asked tentatively.

“Yes,” she replied, upbeat, “but they’re hanging in there. Trying to go about life as best they can under the circumstances.” It was a final reminder, as Pat and I said auf wiedersehen to Frankfurt, that war, displacement, immigration, loss and resilience are not confined to the past.

###

A special note: the story of Block 14 and Lone Fir Pioneer Cemetery inspired my historical novel, Burying My Dead. It’s available as an ebook or you can order a print copy from me at bettie.denny@gmail.com.

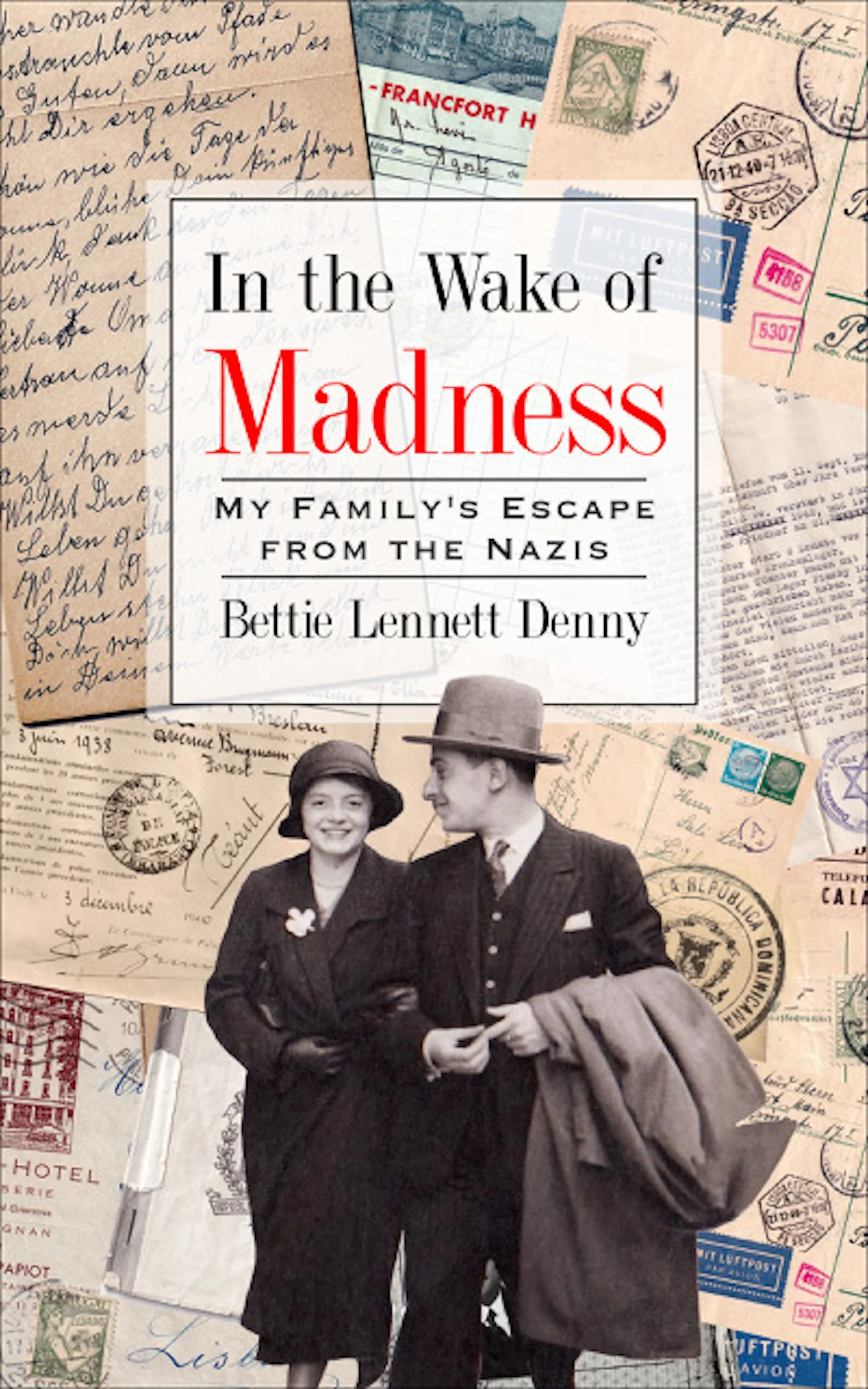

Enjoying this blog? Be sure to read In the Wake of Madness: My Family’s Escape from the Nazis. Click here to get a copy or order at your favorite bookstore.