Discovering Frankfurt

I know. Discovering Frankfurt sounds like the title of a tour book. But it was a journey of discovery because my husband, Pat, and I had few pre-conceived notions other than an undercurrent of fear, a feeling that I should not wear my Jewishness on my sleeve. After all, this was the place my parents were forced to flee from the Nazis. But Frankfurt embraced me in ways I did not expect. My preeminent hope was that I would have a chance to meet Tilman Ochs, a local historian who lives outside of Frankfurt in a hill town called Kronberg. Tilman is an octogenarian and retired schoolteacher who volunteered to decipher my grandparents’ old-fashioned handwriting, allowing me to translate dozens of poignant letters from the tumultuous 1940’s.

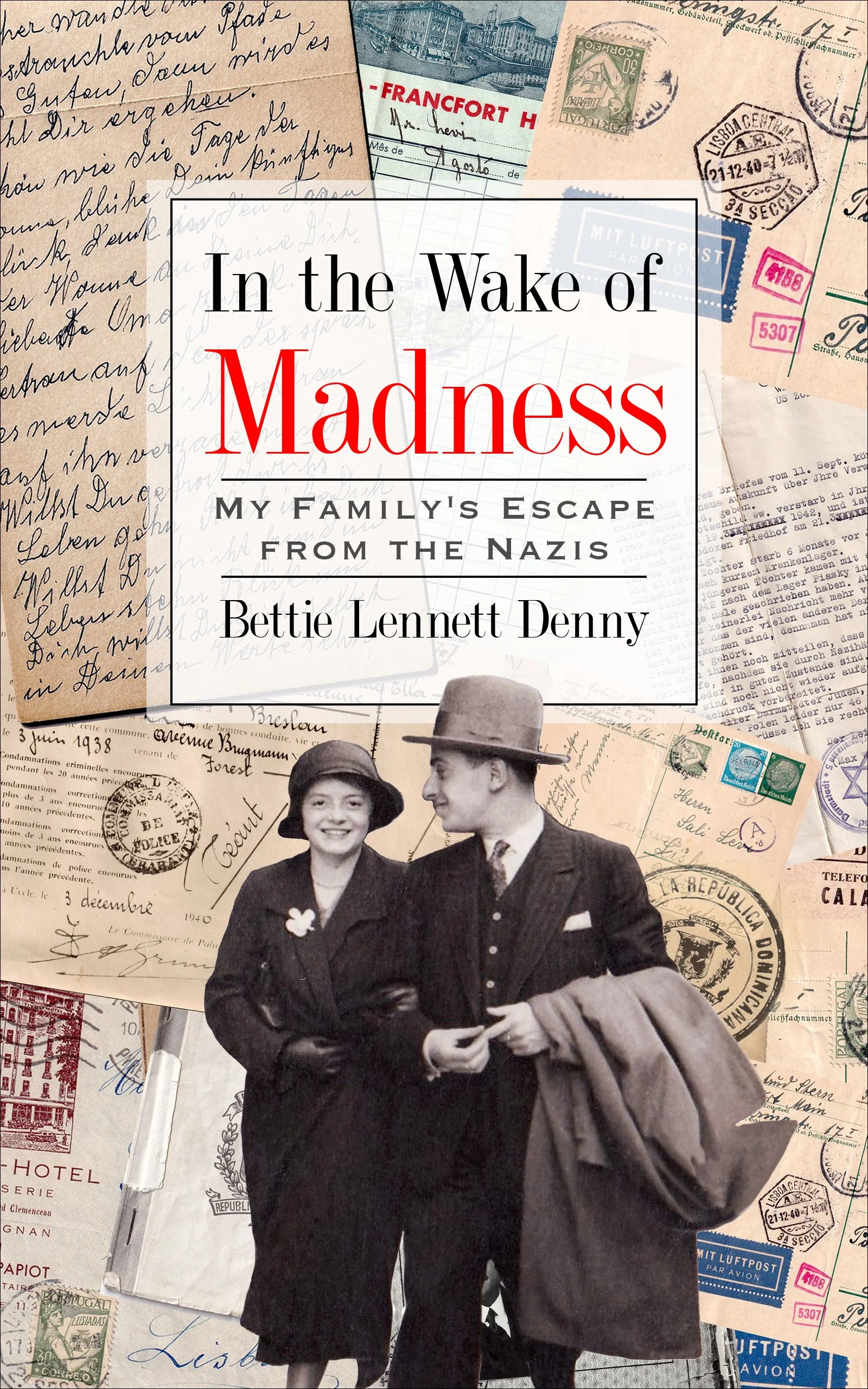

A sample of the documents and letters I discovered when researching In the Wake of Madness. Many of the letters were written in an old German script that few can decipher. I had all but given up hope to ever translate them when I connected with Tilman through my friend and volunteer translator, Andrea Tongue.

If you have read my book, In the Wake of Madness: My Family’s Escape from the Nazis, you know what a miracle it was to have found this treasure trove of documents and to have found Tilman over 5,000 miles away. We had only corresponded via email but his encouragement was the primary factor that led me to seek publication. He called soon after we arrived at our hotel. “How about tomorrow?” he asked eagerly.

The sculpture outside of Jewish Museum of Frankfurt is untitled, but its symbolism of uprootedness is clear.

The following day, Til and his wife, Cristel, met us at the entrance of the Jewish Museum of Frankfurt in a part of town where old and new intermingle. Pat and I waited by a provocative sculpture that aptly captures the dual feelings of Frankfurt Jews including my parents: one of deep connection and the upside-down emotion of uprootedness. Til and Cristel, both non-Jews, had never been to this museum. Upon their arrival, we felt as if we had been adopted.

The museum doesn’t focus directly on the Shoah but on the vibrant everyday life and customs of Frankfurt’s Jewish community, from the Enlightenment and Emancipation around 1800 to the present day, but it ably provides the backdrop for the Jewish struggle for civil rights. It is no surprise that anti-Jewish sentiment has been prevalent for centuries, but it was still stunning to see demeaning quotes from many prominent people long before the era of the National Socialists (Nazis). Museum curators had no problem covering the walls in quotations.

“It is with regret that I discuss the Jews: this nation is, in many respects the most detestable ever to have sullied the earth. ”

“Among the circles of highly educated men who reject any idea of church intolerance or national arrogance there rings with one voice: the Jews are our misfortune!” Heinrich von Treitschke, German historian (1834-1896)

“But what can Spinoza, Mendelsohn, and my noble Jewish friends have in common with Judas Iscariot? One thing should be a source of comfort:…the few noble Jews we’re treating unjustly will think nothing of it, and the rest will receive their due.” Achim von Arnim, German poet (1791-1831)

“As long as the majority of Jews have the limited perspective of Gypsies, they will not be capable of civic equality.” Wilhelm Marr, journalist and German agitator who coined the word antisemitism in 1879 (1819-1904)

“A foreign people cannot acquire the rights that Germans in part only enjoy as a result of Christianity.” Friedrich Ruhs, university professor of history (1781-1820)

Cristel’s eyes filled with tears and then with rage. Like Tilman, she was a child during the Holocaust. Both feel the burden of guilt for being associated with a country that had fostered such sentiments and generated such horror. Today, both follow contemporary politics. It is fair to say that they are worried: worried about the rise of Germany’s right-wing AFD (Alternative for Deutschland) and worried about the authoritarian policies of President Trump.

Despite the long history of anti-Jewish beliefs, Jews struggled for a measure of equality, and Frankfurt became a thriving cultural center for displaced Jews all over Europe. During the Enlightenment, Jews won rights in drips and drabs, and, when Germany came together as an Empire in 1871, Jews were, at least on paper, granted equal citizenship. What grabbed my attention was the vibrancy of the Jewish community prior to the war. In this interim period, Jews became philosophers and poets, doctors and professors, opera singers, painters, and journalists. In one section of the museum, I read dozens of short biographies, painting a picture of the Jewish community of which my parents were a part. Pat recalls photos of Jewish men determined to show their athletic prowess by joining Bar Kochba and Maccabi clubs, a way to fight the stereotype of the weak Jewish man in a time of increasing prejudice and restrictions. The boldness of the women was remarkable. Take, for example, Dr. Martha Wertheimer, a prominent journalist until she was dismissed in 1933; a committed champion of women’s rights, she organized transports of children before being deported in 1942. Or Liesel Simon, an author, actress and puppeteer who escaped to Ecuador but whose husband was murdered at Auschwitz. Or Bertha Pappenheim, a pioneer of women’s rights and social work.

Dr. Martha Wertheimer’s development of the Kindertransport saved 10,000 Jewish children, delivering them safely to England.

What settled in as I explored these lives was an emotional understanding: entwined in the fabric of the larger community, freed from the legal shackles that restricted citizenship prior to 1871, some Jews could not believe that their country had turned on them so dramatically beginning in 1933. They couldn’t believe that this was much more than a blip in history, and, most importantly, that the people around them would accept it. My grandfather’s brother, a veteran of The Great War, was among those who wouldn’t leave – and he paid the price. The lesson felt uncomfortably contemporary. The dilemma was a struggle for every Jew: “Should I stay or should I go?”

When we left the museum, Tilman began a short tour, including a walk in the Römer, the historic public square in Altstadt (Old Town), where we paused in front of the gabled structures that harken back to the 15th century but were actually rebuilt after the bombing of 1944. According to Tilman, many objected to the reconstruction, fearful that it would turn into a kind of Disneyland, but the result is impressive.

Clockwise from upper left: Til, Cristel and a very happy me in front of the Rathaus (City Hall) where my parents were officially married in 1935; a lithograph of the original Rathaus my mom had rolled up in a drawer; a postcard from Bad Ems where they held a religious ceremony two days later, further from Nazi eyes; Frankfurt am Main is nicknamed “Mainhattan” because of its place as the financial center of the European Union.

We posed in front of the Rathaus (City Hall), the place where my parents were officially married in the eyes of the State. Inside I found an exhibit about Jewish customs, inspired, I’m guessing, by the celebration of Passover. In Germany, separation of Church and State is interpreted as “constructive neutrality” that supports positive contributions of various religions. I felt oddly affirmed in my Jewish heritage to find such an exhibit in a public space. The following week, the space was devoted to Easter.

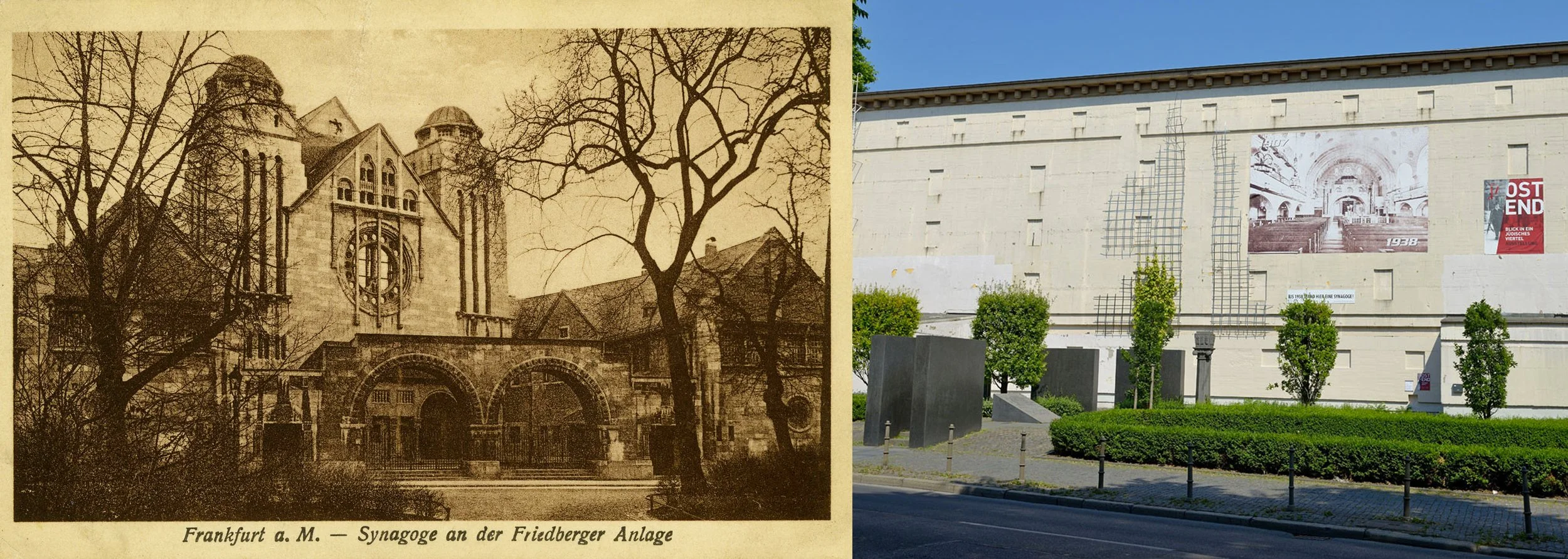

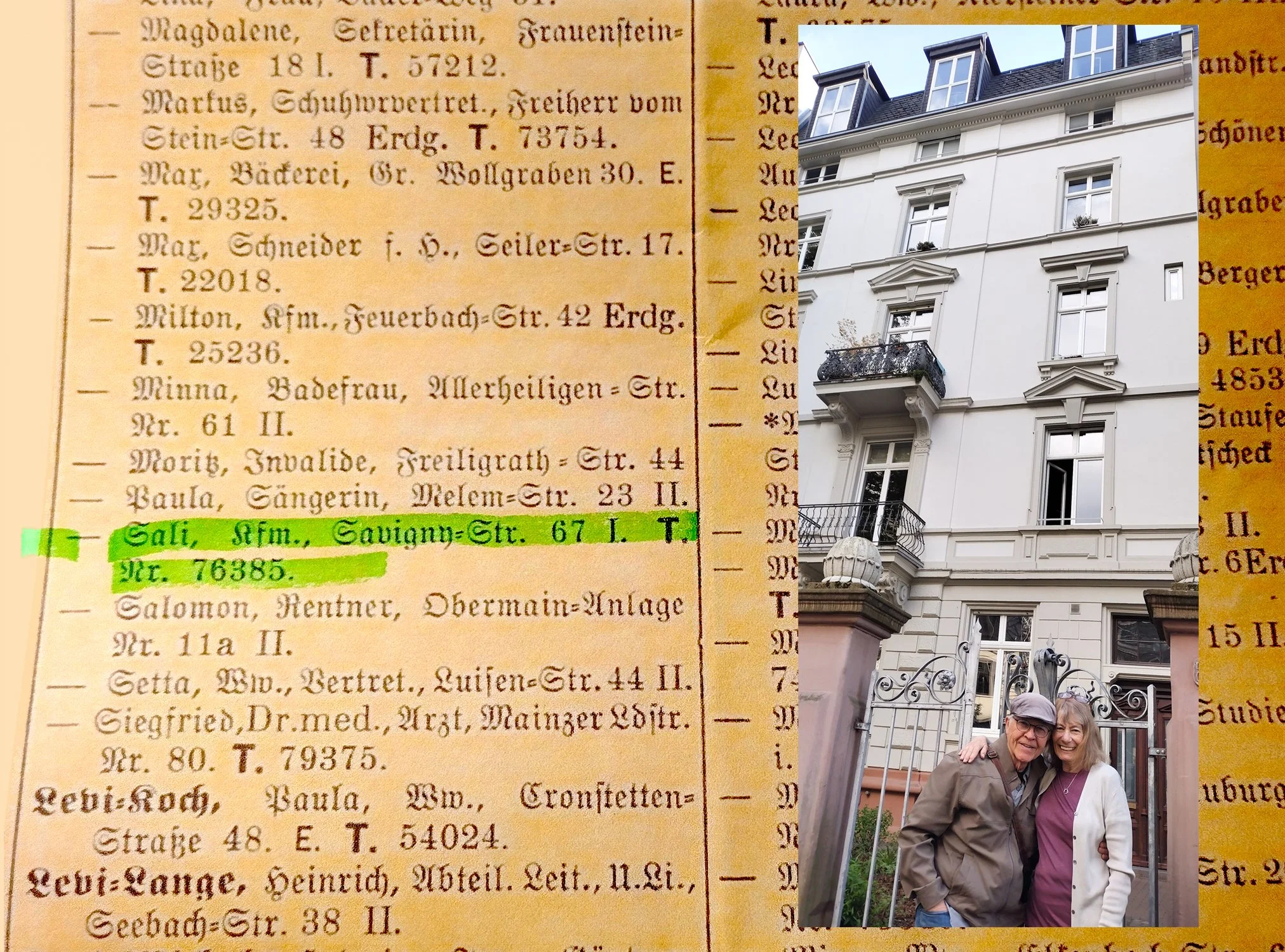

And, then, Tilman surprised me. Ever a researcher, he had discovered a 1914 directory and had taken the initiative to search out the address of my mother’s family - and, in a 1937 directory, found the address of my parents. First, we sought out my grandparents’ place on Seilerstraße. There was no trace of it. That was hardly surprising since well over half of Frankfurt’s buildings were demolished during the war. The synagogue nearby, the grand Friedberger Anlage built in 1907, had been largely destroyed by fire during Kristallnacht in November 1938. A few years later, a high-rise bunker was built on its foundation, offering shelter from Allied bombs for all except the Jews.

Left: the Friedberger Anlage Synagogue before the November 1938 pogrom known as Kristallnacht. Right: the bunker established by the Nazis on that site is now used by the Jewish Museum for ancillary exhibits.

Next, we traveled to 67 Savignystraße, where my parents had lived. My expectations were low, given what we had just seen. But, miraculously, their four-story apartment house still stood proudly, a product of 18th century architecture. On either side were buildings clearly constructed after the war. Cristel asked me if it saddened me to be there, but, honestly, it filled me up to know that my parents had been newlyweds at that very place, that they had found joy there before the heartache.

My father’s name at birth was Sali, as seen above. I was amazed to find my parents’ apartment still intact.

Tilman and Cristel, Pat and I soon parted for the day. We would see them again, in the town of Kronberg, nestled at the foot of the Taunus Mountains which my mother often mentioned. There we followed Til up and down the alleys and into the centuries-old Kronberg Castle. We would conclude the day with hours of talk about life: about the cultural differences between older Germans who feel accountable for their Nazi past and more recent immigrants, who feel disconnected from that history; about fear of Putin and the lessening support of Ukraine and the EU; about the challenges of aging. I promised Cristel that we would take time to see Jüdengasse, a second location of Frankfurt’s Jewish Museum that she had found very moving. When we parted, we knew it was likely the last time we would see each other in person. My eyes welled up with tears as we embraced. They had quickly become friends.

Left: Kronberg Castle photo by Johannes Robalotoff/Wikimedia. Right: Tilman heading down the steep steps that connect layer upon layer of this hilly town.

A 20-minute train ride took us close to our motel. It was already close to ten and, frankly, we were tired. As we headed down the escalator, I turned to Pat and asked nonchalantly, “Do you have the back pack?” Pat looked up at me and shook his head. Frantically, we charged up the escalator, our fellow passengers stepping aside for these two crazy septuagenarians. In his haste, Pat grabbed the handrail in hopes of steadying himself, not thinking that it was going in the opposite direction. It took him down with a thud, the sharp edge of the metal stairs piercing his leg and drawing blood. Yet up we climbed to the top and, lo and behold, our train was still there. Pat held open the door as I searched the seats. Then I heard him say calmly, “Bettie. You’re wearing it.” Yes, indeed. We couldn’t stop giggling for quite a while. Later I thought of how strange it was to laugh in a place where once there was such terror.

###

Have you read my book? In the Wake of Madness: My Family’s Escape from the Nazis is both riveting and relevant - and it makes a great book club selection. Ebooks are available at Amazon. (Choose Amazon at link.) Paperbacks can be ordered at your favorite on-line or brick and mortar bookstore.